If God hadn’t desired repetition,

If God hadn’t desired repetition,

the world would never have been created.

Soren Kierkegaard, Repetition

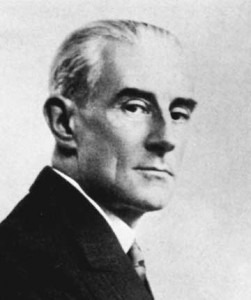

Repetition is essential to music. Indeed, without some form of repetition, there is no rhythm. And few composers have taken this consideration of repetition as seriously as Maurice Ravel did, in his Bolero. His most famous composition was launched in 1928 as a ballet. The universally known theme, repeated over and over again for about 13 minutes, elegantly introduces the different sections of the orchestra in a crescendo, culminating in an extravagant finale. Stravinsky called Ravel “the most precise Swiss watchmaker”, but Ravel’s Bolero is much more than a mechanical exercise in repetition – it is a small musical treatise on the importance of repetition.

First of all, what do we mean by repetition? Not at all monotonous repetition, mindless mechanics, technique without soul. On the contrary, repetition is the core of life: like music, life does not exist without repetition. Soren Kierkegaard explored this better than anyone in his 1843 book Repetition, in which he distinguishes Repetition from Recollection. The latter relates to the endless pursuit of an ideal: we remember an idea, a moment, a trip, a dinner etc. and try to imitate it, try to live it again. The former is the real: true Repetition can only occur not when the external circumstances are similar, but when our deepest self is realised – when we are ourselves, we cannot but repeat ourselves (for we will always be ourselves). Recollection is the ideal, the external, whereas Repetition is the real, the internal.

Repetition, thus, is not the mechanical re-passage that most people say; rather, it is precisely what allows for some originality in our lives, for something unique, for something which is our own. Kierkegaard develops this further in The Concept of Anxiety; “when there is no originality in repetition, it is only habit. The serious man is serious precisely because of the originality with which he repeats himself within repetition”. No meaning can be given to life from outside life: for example, no-one finds true meaning in life by going “on the road”, as the Beat generation would have it. Rather, it is to be found in our everyday actions, in our routine. Meaning is constructed by us at every moment, in our day-to-day lives: the more quotidian the action, the more indicative it is.

The musical parallel here is very strong: it is the difference between music which incorporates aspects or themes from other pieces (to the delight of so many critics who live to identify these hints) and music which revolves around its own core, creating its own meaning. The former is Recollection; the latter, Repetition. Ravel’s Bolero is the ultimate repetition – the instruments all change constantly, but the theme is the same: the software of life must change – and it does, always – but the hardware remains.

The link between the existentialist analysis of Repetition and the musical theme of repetition in Ravel was explored in a superb manner by Claude Lelouch in his 1981 film Les uns et les autres (released in English, tellingly, as Bolero). This epic film is centred on the Bolero: it begins and finishes with it. It is a feast for music-lovers: it tells the story of two generations in four different musical families in France, Germany, Russia and the United States, from the 1930s until the 1980s. Ravel’s piece unites all the threads of what is a very complex narrative. The main theme of the film is repetition, and the Bolero is used to illustrate it – there are also several other hints: that the actors play the main characters and their sons and daughters; that the German pianist believes in reincarnation, for “how can you explain that he could play Rachmaninoff’s 3rd when he was five years old if he hadn’t known him in another life?”. In a moving passage, the film’s narrator asks “Why is the beginning like the end? …Why does Fate play out always in the same way?”.

The self (like music expertise) can only be developed through repetition. When we truly listen to Ravel’s Bolero, therefore, we catch a glimpse of originality in its rough state, of music itself. The Bolero is not a substitute for anything; it is not a mask; it is not trying to be anything else. If, as Kierkegaard said, “the only true happiness is the love of repetition”, the Bolero is the happiest of pieces of music.

Related videos:

Ravel: Bolero, in Les uns et les autres

Maya Plisetskaya – Bolero (choreography by Maurice Béjart)

Photo credit: genedelisa.com