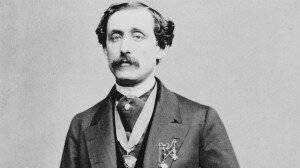

Louis Moreau Gottschalk

Louis Moreau Gottschalk was the original 19th-century musical rebel. Born in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1829, he was a music prodigy, making his public debut at age 11. When he was 13, he went to Paris with his father and applied to the Paris Conservatoire, but was rejected without an audition solely because he was American. The French felt that Americans were best at building steam engines and the head of the Conservatoire, Pierre Zimmermann, dismissed him, saying that he came from a ‘country of railroads but not musicians.’ Eventually, though, he found teachers and at age 16, when he gave his French debut recital at the Salle Pleyel, it was Chopin who praised his talent. Other French composers such as Berlioz and Alkan recognized him as did Liszt.

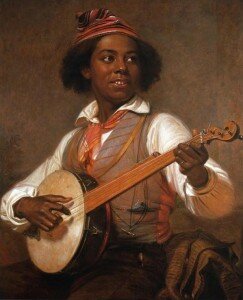

Mount: The Banjo Player (1856)

(Museums of Stony Brook, NY)

Gottschalk returned to the US in 1853 and travelled extensively not only in North America but also the Central and South America. He spent time in the Caribbean and much of his early popularity came from his compositions such as Souvenir de Porto Rico and Bamboula. In Europe, both his talent and his nationality made him an object of interest. When he returned to the US, it was the advance press reporting on his European triumph that brought attention. He was America’s first virtuoso and it was his early death at age 40 that cut short his international career.

Gottschalk’s music might be viewed as an American version of Liszt: highly technical and very virtuosic, but at the same time, Gottschalk had his finger on the pulse of the sentimental and maudlin Victorian audiences that formed his fan base. Many of his musical works had generic roots that had parallels in the artistic world of genre art. Some of his works, such as The Dying Poet, became staples of the accompaniment for silent films in the early 20th century.

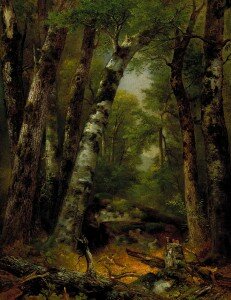

Asher B. Durand: Woodland Glen (ca. 1859)

(Smithsonian American Art Museum)

The Banjo (1853, 1855) brought the knowledge Gottschalk had of Latin American music to his American audience. The banjo, at the time, was also an instrument of the minstrel show, a popular variety show that included comic skits, variety acts, dancing and other performances performed by white people in blackface makeup. By the mid-19th century, the minstrel show was the national art form in America. Gottschalk understood the value of the instrument and made a work of his own reflect it. Within the work, you will hear echoes of other American songs, such as Stephen Foster’s Camptown Races and Roll, Jordan, Roll. In genre painting, artists such as William Sidney Mount also sought the same audience.

Gottschalk: Le BANJO, Op. 15 (Claudia Schellenberger, piano)

Asher Brown Durand’s painting Woodland Glen (ca. 1850), a model of the landscapes that the Hudson River School is known for, is thought to have been the basis for Gottschalk’s Forest Glade, Op. 25 (1853).

Gottschalk’s The Gleaner / La Glaneuse of 1848, now lost, anticipates the painting of the same name by Millet in 1857. His mazurka La Moissoneuse / The Reaper, Op. 8, of 1850, offers an autumn landscape, with the peasants at work.

Millet’s Gleaners shows the peasants who combed through the field after the harvest, picking up what was left. The contrast between their back-breaking work in the nearly empty field and the bountiful harvest piled behind them, still shining in the sun, underscores the difficulty of their sunset task. At the same time, the gleaners aren’t working under any oversight – they work at their own pace, each in their own way – and are independent in their own way.

Millet: Gleaners (1857) (Musee d’Orsay, Paris)

These parallels let us see how much Gottschalk’s music was as much a genre as the genre paintings his works were associated with. Audiences sought the narratives behind the works that surrounded them: just as much as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin could be read as an album of emotional sketches or a song cycle of the melancholic sort, so Gottschalk’s Pastorella e cavalliere, op. 32, was read as a narrative of farm girl versus the city slicker.

In 1855, while on tour in New York State, he met the sculptor Erastus Dow Palmer. A parallel has been drawn between the narrative of Gottschalk’s The Last Hope and Palmer’s statue First Disappointment (1861). Palmer sculpted the disappointment of one of his daughters who, after following the hatching and rearing of a nest of birds, was overcome with grief to find the empty nest after their departure.

Palmer: First Disappointment (1861)

(Walters Art Museum)

Written during a trip to Cuba in 1854, Gottschalk’s piano meditation The Last Hope was both his best-selling work, his most famous salon piece, and has never been out of unavailablity since its composition. After Gottschalk toured with the piece, it appeared as sheet music, on player-piano cylinders, on piano rolls, on music boxes, and on recordings. In 1888, it was the source for the hymn tune ‘Grace’ and then was the basis for four different Protestant hymns, including ‘Holy Ghost With Light Divine’ and ‘Father of Eternal Grace,’ The manner in which Gottschalk’s lovely melody is surrounded contrasting low voices and the stratospheric angel-like flourishes above brings an almost celestial calm. The work is a masterpiece of sentimentality.

Gottschalk: The Last Hope (Roger Lord, piano)

Gottschalk started writing music criticism, following the model of Liszt and Berlioz. He was approached by the Morning Times to write their “Crotchets and Quavers” column under the pen name “Seven Octaves.” He wrote not only about music but also about New York architecture, popular minstrel shows, theatre, and contemporary painting and sculpture, referring to his friend, Erastus Dow Palmer as “the immortal Palmer.” When he discussed Palmer’s work, it was with the intention of revealing the program of each piece, i.e., ‘to make explicit the narrative underlying the work.’ Again, this shows his awareness of his audience’s desire for stories, sentimental or mawkish, but very much a 19th century desire.