Prokofiev in Chicago, 1919

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) started experimenting with a number of short piano works in 1915, completed them in 1917, and gave them their first public performance on 15 April 1918 in Petrograd/St. Petersburg. At a private performance some months before, the Russian poet Konstantin Balmont was so inspired that he composed a sonnet on the spot. This poem inspired Prokofiev to use one of the lines of the poem, which he called ‘a magnificent improvisation,’ as the title for his piece, Mimolyotnosti.

Balmont’s poem, ‘I do not know wisdom,’ uses the word ‘mimolyotnosti’ as the centre of two important lines. The word, which means ‘transiences’ in English, was used in its French translation, ‘visions fugitives’ and that same translation has been applied to the title of Prokofiev’s work.

I do not know wisdom — leave that to others —

I only turn transiences/fugitive visions (mimolyotnosti) into verse.

In each fugitive vision I see worlds….

Balmont had been a source for some early songs by Prokofiev, starting with ‘The White Swan’ and ‘The Wave,’ dating from 1909. Balmont’s texts were also set by Tcherepnin, Myaskovsky, and Stravinsky, among others.

The fugitive visions seem to be based around a fugitive tonality – Prokofiev is experimenting with modernism in these works and, at the same time, experimenting with much older forms. The work begins with a rather thoughtful Lentemente, it seems to float, almost in a kind of Debussy-like fashion.

Sergei Prokofiev: Visions fugitives, Op. 22 – I. Lentemente (Tedd Joselson, piano)

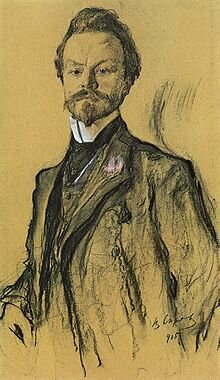

Valentin Serov: Konstantin Balmont (1905)

As a contrast, the following Andante brings in sharper dissonances, giving it a more modern (for the early 20th century) feel.

Sergei Prokofiev: Visions fugitives, Op. 22 – II. Andante (Tedd Joselson, piano)

One of the older forms, ternary, is used for the next Allegretto. The middle section moves away from the opening motion, becoming brighter.

Sergei Prokofiev: Visions fugitives, Op. 22 – III. Allegretto (Tedd Joselson, piano)

The following movement are sometimes more animated, sometimes more dance-like. The Molto giocoso almost sounds like a bit of Ravel. Prokofiev wrote that in the work are a ‘peal of bells’ celebrating the wedding of a friend, Lida Karneyeva.

Sergei Prokofiev: Visions fugitives, Op. 22 – V. Molto giocoso (Tedd Joselson, piano)

The most striking piece is the second to last. The 19th vision, Presto agitatissimo e molto accentuate, was described as Prokofiev as having been written while he was in Petrograd / St. Petersburg in 1917 in the throes of the beginning of the Russian Revolution:

The February Revolution found me in Petrograd…, hiding behind house corners when the shooting came too close. Piece XIX of the Visions fugitives written at this time partly reflected my impressions—the feeling of the crowd rather than the inner essence of the Re¬volution.

Sergei Prokofiev: Visions fugitives, Op. 22 – XIX. Presto agitatissimo e molto accentuato (Tedd Joselson, piano)

One of the first reviewers thought these works were quite different from Prokofiev’s regular style, noting, ‘Prokofiev and tenderness – you don’t believe it? You will see for yourself when this charming suite is published.”

The work isn’t all charming – there’s real agitation in the 14th and 15th pieces, Feroce followed by Inquieto, but all in all, it’s a kind of 20th-century Russian Impressionism, following the French 19th-century model. It’s not the Prokofiev you might know from Lieutentant Kijé and the like, but it is very much the musical musings of an accomplished pianist and composer.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Nikita Mndoyants Plays Prokofiev’s Vision Fugitives No. 14