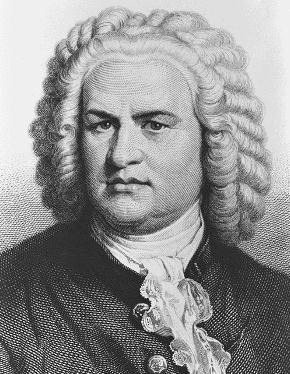

| Bach, the composer as intellectual

But all at once it dawned on me that this Vladimir Nabokov, Pale Fire |

If prayers begin by invoking God’s greatness, a series of articles on music should begin with an invocation of the genius of Bach. But how does one write about Bach? So many are the superlatives applied to him that any word one might add feels superfluous, almost sacrilegious. Jorge Luis Borges felt the same difficulty in his poem To Johannes Brahms:

I, who am an intruder in the gardens

You have prodigated on the plural memory

Of the future, wanted to sing the glory

That lifted your violins up to the blue. (…)

My servitude is the impure word (…)

Dispossessed even of Borges’ “impure word”, or of his poetic genius, I must resign myself to an intellectualised reading of Bach, at least in the beginning; speaking of Bach, one cannot stay only in the mind for too long.

Edward Said wrote an essay entitled ‘Glenn Gould, the virtuoso as intellectual’ (collected in the excellent Music at the limits, forwarded by Daniel Barenboim), in which he argued that Gould’s interpretation of Bach produced such a powerful re-conceptualisation of our relationship with the keyboard that his achievement was as much an intellectual as an artistic one. The same applies, to an even larger extent, to Bach.

Bach’s absolute key, that particular chanson which Proust said characterises each artist, is, as Said argued, the combination of rhythm and polyphonic statement. Bach’s music is not only about the complete mastery of counterpoint, but rather it is about how he transcended baroque form to construct a cascade of beauty. With each flow of music, a new layer of perfection is added.

On the one hand, this is decidedly un-modern, in that it is not dialectical. Modernity requires thesis, antithesis and synthesis – whether in art, politics or philosophy: modernity’s birth, after all, is marked by the ultimate historical synthesis, the French Revolution. In music, this was expressed in the passage from classical to romantic. Beethoven’s chanson, in which he excelled, was all about dialectical tension; introduction (first movement: the genealogy of the problem), a theme (second movement: thesis) struggling with another theme’s obsessive development (third movement: antithesis), culminating in an apotheotic finale (fourth movement: synthesis).

In Bach, however, the point is not the synthesis; the multiple themes he develops do not come together in a climatic release. Rather, the point is the eternal interplay between them: the Goldberg Variations must rank alongside Montaigne’s Essays as attempts to look at a problematique from all possible angles – and are at least as revolutionary from a philosophical perspective. This idea of seeing a “web of sense”, as Nabokov wrote, emerging not from a dialectical process, but from the nature of counterpoint itself is, in part, a very classical one, drawing back to Aristotelian rhetoric. The point is to move away from a dialectical attempt to discover the right answer and rather focus on trying to frame the correct question.

On the other hand, Bach’s approach is, if not post-modern, incredibly suitable for our times. Many music students lament his rigidity (even Chopin, in the almost certainly apocryphal, but nevertheless illuminating, quote “Bach tries to measure the distance between the stars; I try to reach for them”). But Bach is not caged in by form: the fact he goes beyond baroque polyphony and complements it with substantive rhythm is what makes his music lend itself so well to jazz, for instance. In internalising the alpha and the omega, Bach reaches that nirvana state from where true improvisation can originate. From Nina Simone’s completely Bachian piano solo in Love me or leave me to Jacques Loussier’s brilliant interpretations, the beauty in his writing frees the music from the rigidity of form and creates the most liberating, sensuous and soul-affirming feelings.

After all, what can be more adequate for our over-compartmentalised times than music that draws on the connections of different points? Bach is, therefore, more than a composer: he is a web of sense, in which our own internal contradictions, counterpoints and flashes of divinity co-exist. He did not need to reach for the stars: he had already gone far beyond them.

Related video :

Nina Simone : Love me or leave me

Jacques Loussier