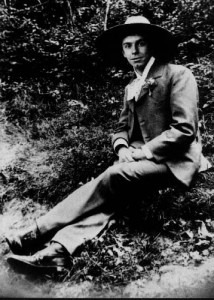

Alexander Scriabin

Credit: http://alanfraser.net/

Athletic awkwardness none withstanding, Scriabin channeled his feelings for Natalya into a mystical poem, which he eventually set to music as well:

Were I by sweet dreaming

To dwell within thy soul,

Were I to turn thy fair head

To great thoughts of creation,

I would, dear friend,

Reveal to thee

A universe of delight.

Entitled “Romance,” the manuscript was only found after Scriabin’s death and there is no evidence to suggest that Natalya ever heard it. In March 1891, Natalya’s mother intercepted a love letter and summoned Scriabin. Before she could say a word, Scriabin burst out, “Natalya and I consider ourselves engaged to be married and have to for some time.” Hardly surprising that he was forbidden to enter the house ever again. Scriabin was devastated and he communicated to Olga, “Don’t take away my little Natalya. Don’t deprive me of my muse. I love her with that pure, ideal love with which one loves only once in a lifetime.” Olga eventually agreed to become the messenger, ferrying secret notes and letters between the lovers.

Natalya Sekerina

Stormy clouds were gathering over the relationship when the couple attended the 1894 debut recital of Josef Hofmann in Moscow. Natalya was mightily impressed, much to the displeasure of Scriabin. Hofmann was also an expert ice skater and Natalya and Hofmann “sailed around the rink gaily chatting while Scriabin became fearfully depressed.” At a school ball shortly thereafter, Natalya danced every dance, while Scriabin—who thought of dancing as a vulgar, unpleasant and meaningless activity—stared at Natalya’s empty chair. From that point onward, Scriabin’s messages become rather incessant, “Hear me out! Listen to this voice of a sick and tormented soul. Remember and pray for the man whose entire happiness is yours and whose entire life belongs to you.” He even composed the rich and melodious Etude Op. 8, Nr. 8 for her, and attempted to arouse her jealousy by publically holding hands with a number of young ladies. Apparently, Scriabin’s renewed proposal of marriage was met by Natalya’s flat rejection, “I am not marrying you, because I love you less than I did at first.” And that, as they say, was the end of the relationship. Natalya eventually married the judge Nikolai Markov, and Scriabin turned his attention to Vera Issakovich; more on that relationship next time.

Alexander Scriabin: 12 Etudes, Op.8 Nr. 8