Casals

I sat very close to him with just barely enough space to bow. I chose to play the prelude to the Bach Suite No. 1 in G. While I played through the whole movement, I glanced up at him several times, but he seemed to be in a stupor, his arm hanging over the side of his wheelchair, his body listing to the right. When I finished the last chord with a flourish my dad suddenly sat bolt upright and said, “Janetke! Why did you slow down there so much? Move the tempo. Play softer in the middle. Play it again!” I think he liked the second time much better.

Janos Starker

Credit: http://i.telegraph.co.uk/

The suites were quite unknown until a 13-year-old young boy, Catalan cellist Pablo (Pau) Casals, happened upon a yellowed edition of them in a thrift shop in Barcelona, Spain — an edition by cellist Friedrich Grützmacher of 24 études fame. In Casals’ book Joys and Sorrows, he indicates that he began each day with Bach without fail.

Mysteriously, unlike Bach’s Solo Violin Sonatas, the original manuscript to the Bach Cello Suites disappeared. What remains is a hand-scribed copy by Anna Magdalena Bach, Bach’s second wife, but none of the articulations, slurs or intended dynamics were written down. Hence there is no definitive interpretation of the works and performances vary quite a bit. They are believed to have been composed around 1720.

The great cellist Pablo Casals was known for his discovery and performances of the suites, but even after studying the suites for a lifetime he didn’t feel ready to record them until the 1930’s when he was 60 years old. I performed both the third and fifth suites in recitals during my teenage years — from memory and with panache when, like many 19-year-olds, I thought I knew everything.

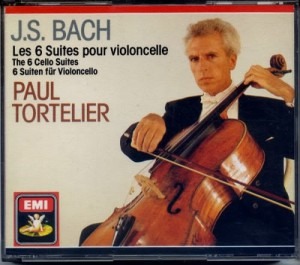

The great cellist Pablo Casals was known for his discovery and performances of the suites, but even after studying the suites for a lifetime he didn’t feel ready to record them until the 1930’s when he was 60 years old. I performed both the third and fifth suites in recitals during my teenage years — from memory and with panache when, like many 19-year-olds, I thought I knew everything. When Casals recorded all six suites, a project completed in 1939, he became the first of a long line of cellists to record them. Today young cellists have the advantage of being able to compare recordings of all the greatest cellists. This list reads like a who’s who of cello virtuosos — Janos Starker, Anner Bylsma, Paul Tortelier, Pierre Fournier, Mstislav Rostropovich and more recently Yo Yo Ma, Steven Isserlis, Maria Kliegel and Matt Haimovitz. But Casals’ version is still regarded as having set the standard. There are a few cellists that have performed all six suites in one or two performances such as Colin Carr and Pieter Wispelwey — talk about a marathon!

The Bach Suites are the high bar set that distinguishes cellists. In fact, most cello auditions — and violin and viola auditions for that matter — require some solo Bach to be performed in addition to a concerto, for orchestral positions, entry into college music programs and for International competitions.

The suites all begin with a prelude, an introductory organ-like movement, followed by several dance movements including an allemande, courante, sarabande, two menuets and a gigue. In the 3rd and 4th Suites the minuets are replaced by bourrées and in the 5th and 6th Suites they are replaced by gavottes.

It’s a feat of concentration to perform the suites. Not only are they lengthy, you are alone on the stage with no one to rely on, so the memorization alone is a formidable proposition. My teacher Janos Starker once told me the following story. He was to perform the popular Suite No. 3 in C major. After a complex travel schedule halfway around the globe he appeared somewhat bedraggled and with jet lag for the recital. He launched into the suite but soon found his mind wandering just a bit. After he had played a chord at the end of a phrase common to several suites, he realized with dismay that he was playing a movement from a different suite. Somehow he found his way back to C!

There are more than twenty editions of these works. Janos Starker himself “thought of asking J.S. Bach how he wanted his suites played, which made the hereafter seem palatable, even desirable.” But he decided “to leave the Master in peace” as he discovered after a lifetime of playing and recording them that, “one of the certain signs of a masterpiece is its ability to withstand presentations of all kinds and still remain a masterpiece. The thousands who have found rewarding musical experiences with these works had limitless views on phrasing, dynamics, and concepts… Playing Bach is a process of search and change with no end in sight.”

I still perform the prelude to the 1st Bach Suite. I always discern something new, but I never forget when I played it for the last time for my dad.

Bach: Suite No. 3 Prelude (János Starker)

Bach: Suite No. 3 (János Starker)

Bach: Prelude to the Suite No. 1 in G (Yo-Yo Ma)

Casals: rare video of the Suite No. 1 Sarabande, Menuet I and II and gigue from 1954

And a very neat outdoor performance of the prelude to suite No. 6 with Matt Haimovitz

And Janet performing Suite No.1 Prelude

According to Professor Martin Jarvis in his scholarly book ‘Written by Mrs Bach’, the six cello suites were actually composed and written by Anna Magdalena, not just copied by her. She was supposedly a great artist in her own right but her legacy was suppressed by Bach’s sons (from his first wife) after she passed away. Do you concur with this research?