On my recent European lecture tour, I was fortunate to hear several concerts in magnificent Baroque churches on Baroque organs, including one in the church of the former Cistercian monastery of St. Urban, Switzerland and one in the St. Francis Church in Prague. Not only was this a musical experience to treasure, hearing the works of the greatest organ music composers of their time, (Frescobaldi, Pachelbel, Muffat and Johann Sebastian Bach) played on original instruments, but experiencing it in an architectural space specific to the period.

In particular, J.S. Bach’s architectural musical thinking made me think of the relationship between architecture and organ music not only during Baroque period, but through the ages. Over the course of the next few months, I will concentrate in these articles on the invention and development of the organ, the ‘Royal’ instrument, throughout history, from its beginning in antiquity to the present day, but will then focus more on the architectural thinking at play specifically during the Baroque period — the ‘Golden Age of organ building and organ music’.

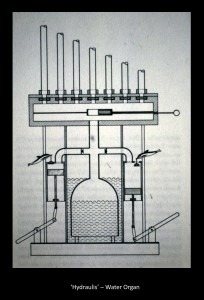

The earliest known pipe organ, called hydraulis, was invented in the third century B.C.E. by Ctesibius, a Greek engineer, in Alexandria, Egypt. This ‘water organ’ continued to be in use in Ancient Greece and in the Roman Empire during gladiator games and other public spectacles. Interestingly enough, women were often the organists, as witnessed by inscriptions on ancient sarcophagi lauding women’s skill in this role.

Several centuries later, the ‘pneumatic’ organ, which depended first on an inflated leather bag and then later on bellows to generate its wind power, appeared in Byzantium. Cicero, Seneca and Vitruvius wrote about this new instrument, whose ‘voces hydrauli’, a palette of sounds, they compared to delicacies of scent and taste. The Roman Emperor Nero supposedly had one of these pneumatic organs built for him. In fact, the name ‘organ’ comes from the Roman word ‘organum’, which in turn is derived from the Greek word ‘όруаѵᴏѵ’ (‘organon’), i.e., ‘instrument’.

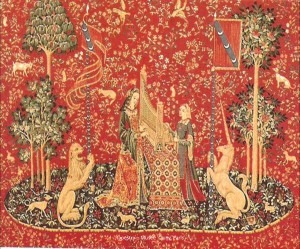

Portable organs (portative and positive organs) were developed in the Middle Ages. We see depictions of such organs with real keyboards in medieval illuminated manuscripts and tapestries. Their portability made them very useful as accompaniment to sacred and secular music, dances and songs. During the early Middle Ages, the church fathers initially prohibited music during church services, but it was later allowed after St. Augustin and St. Thomas Aquinas considered organ music as ‘stirring the soul and lifting it to the heavens’.

Beginning in the 12th century, the organ began to evolve into a more complex instrument capable of producing different timbres. Early organs, installed in churches, were covered by canvas which could be lifted by pulleys. The different keys were rather difficult to play. In fact, fists had to be used to produce a sound, hence the expression in German: “die Orgel schlagen” (to beat the organ). The late 13th century saw the development of fixed wooden organ encasings, which looked like miniature Gothic winged altars and treasure chests, decorated with beautiful paintings, imitating the Gothic architectural style with pointed arches, canopies and Gothic ornamental carvings and decorations.

In the Renaissance era, the organ continued to develop from one keyboard (‘Manual’ in German) to multiple keyboards as well as a pedal board (an extra keyboard with long pedals manipulated by a player’s feet), with stops and couplers imitating many instruments of an orchestra (trumpet, clarinet, flute, violin). The various possibilities of their combinations resulted in a great variety and complexity of sound.

The polyphony of Renaissance music, with its rich texture, progression of chords and blending of multiple “voices”, was well suited to these new Renaissance organs, which in turn reflected the harmony and balance of Renaissance architecture.