What Is the Meaning and Use of Rubato?

Tempo rubato in music – literally “robbed” or “stolen time” in Italian – refers to a subtle slowing or speeding up of tempo. It is most closely associated with the music of Frédéric Chopin, his friend and fellow composer Franz Liszt, and other composers of the Romantic period, but we can also add tempo rubato, and similar effects, to music of any period – and indeed any genre (classical, jazz, pop, etc.). In fact, it helps music to sound natural: music with a very strict, metronomic pulse (beat), with no sense of space or shape within phrases or sections, would be dull and monotonous, both to listen to and to play. Just as the human voice has changes in pitch and dynamics, tempo and cadence, so playing with rubato gives music expressive freedom, allowing it space or room to “breathe”.

Tempo rubato in music – literally “robbed” or “stolen time” in Italian – refers to a subtle slowing or speeding up of tempo. It is most closely associated with the music of Frédéric Chopin, his friend and fellow composer Franz Liszt, and other composers of the Romantic period, but we can also add tempo rubato, and similar effects, to music of any period – and indeed any genre (classical, jazz, pop, etc.). In fact, it helps music to sound natural: music with a very strict, metronomic pulse (beat), with no sense of space or shape within phrases or sections, would be dull and monotonous, both to listen to and to play. Just as the human voice has changes in pitch and dynamics, tempo and cadence, so playing with rubato gives music expressive freedom, allowing it space or room to “breathe”.

When listening to music, the audience wants to be “surprised” or “satisfied” by what they hear, and when we are playing, we should be aware of musical “surprises” within the music (unusual chords, piquant or unexpected harmonies, changes in articulation – staccato/legato/accents) as well as examples of “satisfaction” (resolutions, full cadences, returning to the home key etc.). We can highlight these by the use of rubato – arriving at a note or end of a phrase sooner or later to achieve either surprise or satisfaction.

Johannes Brahms: 3 Intermezzos, Op. 117 – No. 2 in B-Flat Minor (Radu Lupu, piano)

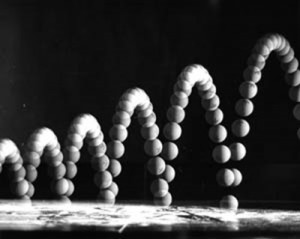

Rubato is not always written into the score as a musical sign, so it is up to us, as the performer, to decide where it might be most effective to alter the tempo of the music slightly. As a simple rule of thumb, we generally slow down at the end of a piece, or the end of a section – unless the composer tells us otherwise with a marking such as accelerando (getting faster) or stringendo (pressing forward, which suggests an increase in speed and a greater sense of urgency in the music). When thinking about slowing down towards the end of a phrase or section in music, imagine the bounce of a ping-pong ball – but in reverse: it is the gradual pulling back of tempo that can be most effective.

Sometimes, we might want to increase the tempo slightly to emphasise a crescendo or to suggest more drama or urgency in the music. This can be particularly effective with a run of notes in a rising scale or arpeggio and can create the effect of the music being allowed to “take flight”.

Accents in the music ask us to consider why the composer has put it there. Is it simply to spotlight a chord, or a particularly note? Or perhaps the composer wants to create a surprise for the audience? Rather than simply playing the note with extra force/emphasis, experiment with placing the note fractionally later: the tiny delay creates a far more dramatic effect than just hammering the note. Try a similar technique with an unusual chord or dissonance – again, that fractional delay adds drama and makes the resolution (when the music moves to a more familiar chord, or the home key) far more satisfying.

We can learn a lot about rubato by listening to singers. The human voice adds natural shape to a musical phrase or melody: as notes rise up the register, so the voice rises fractionally in dynamic. When practising, singing a phrase and then re-imagining that sound on our own instrument can help shape a phrase with natural rubato.

The most natural rubato comes from within the player: it is hard to teach, and for it to sound convincing, it should always feel unforced and uncontrived. Don’t be tempted to mess around with the tempo too much: it is important to retain an underlying sense of pulse and to remember that rubato is “stolen time’. As one of my teachers used to say, “you have to give it back eventually!”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Evgeny Kissin plays Chopin Ballade No. 1

Thank you for this well-articulated, valuable statement. Unfortunately the broad application of rhythmic freedom is misunderstood or resisted in this metronome-obsessed age. Applying early 20th-c. reactioanary aesthetics across the board can distort the style of certain repertoire. The problem is complex in piano chamber music where the pianist is often obliged to defer to instrumental techniques. The music at hand must guide interpretive decisions.

Actually, rubato was NORMAL a 100 years ago. Brahms was in for his time playing very metronomical, but recordings shows wild “rubatos”. Listen to Rachmaninoff. Or Furtwangler.

Nothing more boring than a metrum, unless you are playing a military march.