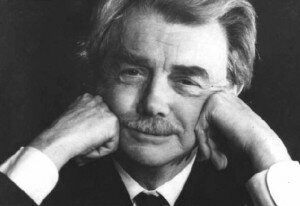

Heinrich Neuhaus

What is the Russian sound, or French style in piano playing? What differentiates a pianist who was taught in the English piano tradition from one who studied in Germany?

The history of piano playing is built from a large network of piano “dynasties”, which reflects a wide variety of approaches to technique and interpretation. Many of the significant pianists and pianist-teachers of the 19th and 20th centuries passed their knowledge and skills to subsequent generations. In turn, those younger players taught the next generation and so a pedagogical and pianistic lineage was established, often with distinct national characteristics. With obstacles to swift and easy communication between countries, coupled with isolationist attitudes, local pedagogical and pianistic practices became the rule in certain places, such as Russia, and these practices became more clearly differentiated between different places or “schools” of piano technique.

Until fairly recently, it was possible to differentiate between these national schools of piano playing. They each emphasised different approaches and connections to piano technique, historical tradition, and artistic and musical ideas, and displayed different areas of strength in the standard repertoire.

The Russian Piano School

The Russian music education system has always been rather shrouded in mythology and outsiders have tended to regard the Russian approach as mechanical, with an extreme emphasis on highly-honed technique over musicianship. Critics of the Russian School point to an emphasis on power in playing, which can be overwhelming, and lacking in light and shade, and an undue focus on producing competition winners, which is of course good for national prestige.

Kissin plays Rachmaninoff

In fact, the Russian School is notable for its full orchestral, projected sound, physicality in playing (an emphasis on use of the arms which drag the hands up and down the keyboard) and the ability to focus talent from a very young age (the result of a national network of specialist state music schools where students learn the rudiments of music in detail). The great pianist-teachers such as A. B. Goldenweiser and Heinrich Neuhaus sought to discover and encourage these characteristics in their pupils, and the Russian Piano School has produced many outstanding pianists including Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev, Richter, Gilels, Ashkenazy, Leonskaja and Pletnev – all musicians who display prodigious and immaculate technique, passion, dramatic power, intense emotional expressiveness and physical vitality in their playing. Younger graduates of the Russian School include Evgeny Kissin, Rustem Hayroudinoff, Denis Matsuev, Daniil Trifonov and Anna Tsybuleva.

Daniil Trifonov plays Chopin

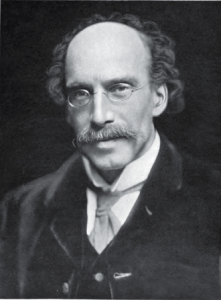

Marguerite Long

The French Piano School

The French School is known for fastidiousness in fine details and a focus on the fingers (rooted in the grand tradition of the Clavecinistes as personified by François Couperin), resulting in suppleness of attack, supreme control in rapid detaché and jeu perlé passages, and great clarity and transparency of sound, coupled with elegance, deft execution, grace over power and aesthetic over emotion. The music and teaching of Fryderyk Chopin undoubtedly influenced the French School’s emphasis on touch, flexibility and a certain emotional restraint, while French piano manufacturers such as Pleyel (whose pianos Chopin favoured) produced instruments with a lighter action more akin to that of the harpsichord which responded to a piano technique founded on articulation and finger suppleness rather than upper body strength.

With Debussy and Ravel, both significant heirs to Chopin, fine finger technique became the vehicle for highly articulated playing to produce myriad of musical colours and textures.

Maurice Ravel: Gaspard de la Nuit – I. Ondine (Alexandre Tharaud, piano)

Important exponents of the French School include Camille Saint-Saens, Alfred Cortot, Marguerite Long, Olivier Messiaen, Yvonne Loriod, Dinu Lipatti, Yvonne Lefebure, Pierre Boulez, Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Pascal Rogé, Hélene Grimaud, Cedric Tiberghien and Alexandre Tharaud.

J.S. Bach: Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006 – I. Prelude (arr. Rachmaninoff for piano)(Hélène Grimaud, piano)(

Tobias Matthay

The English Piano School

The English School of piano playing developed in the early part of the twentieth century, of whom Tobias Matthay was a significant figure. He taught, amongst others, Myra Hess, Harriet Cohen and Harold Craxton, who in turn taught Stephen Bishop Kovacevich, Denis Matthews and Peter Katin respectively. Other exponents of what can be considered an English style of piano playing include Clifford Curzon, Cyril Smith and Phyllis Sellick. John Ogdon and Peter Donohoe, two giants of British and international pianism, broke free of this tradition to forge their own distinctive sound and approach.

Matthay advocated proper piano touch and release, analysis of arm movements, and an understanding and appreciation of arm weight coupled with relaxation and effortless suppleness at the piano, and a knowledge of the mechanics of the instrument itself. He regarded technique as a musical objective, and believed that technique and interpretation should always go hand in hand.

Alongside Matthay’s approach, the influence of Clara Schumann on English pianism cannot be ignored with Solomon Cutner (who performed as ‘Solomon’) as the epitome of this: refined technique, but with some limitations specifically in terms of notational accuracy.

Touch and sound are probably the most important aspects of English pianism together with a quiet intensity, sensitivity and an intellectual approach to interpretation, which has led some British pianists to be regarded as cool or aloof in their playing.

Of course, no one national piano school had a totally homogenised approach nor sound, since individual teachers working within these traditions would each bring their own personality and approach to their teaching and the sound their students produced, and thus ‘schools’ also arose around singular pianists and pianist-teachers – for example, Theodor Leschetizky, Heinrich Neuhaus or Nina Svetlanova.

In the last 20 years in particular, as communication has become so much easier and information far more widely available, such distinctions have largely disappeared as pianists and teachers around the world synthesise characteristics of these national piano schools and leading pianist-teachers from an earlier age to create what we might call an “international piano sound”. Alongside this, open masterclasses, in music schools and via platforms such as YouTube, international piano competitions, the easy availability of very high-quality recordings, the expectations of audiences and juries has led to a certain “standardization” in piano playing and today it is rare to hear someone described as having come from the “French school” or “Russian school” of pianism, though many of today’s pianists had teachers who can trace a lineage back to some of the leading exponents of these schools.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Clifford Curzon plays Schumann

The article is not complete, exist the famous italian school!!!

What about the German school?

The article is quite superficial. It is confusing the “schools” of technique with a concept of stylistic interpretation.

Why don’t you write an article? the article was clear for a good reader and for those with experience in the area.

Enjoyed Kissin, Trifonov, Curzon. Interesting article too, and there is much, much, much more to be said about different “schools.” One day!

I am skeptical. A blind test would be interesting. I think that piano playing is more universal, the pianists play and learn worldwide, a Russian pianist can study in the USA, where there are a british teacher.