Fin-de Siècle Vienna’s ‘Second Generation’ Art and Music

In his opus, ‘Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften’ (The Man without Qualities) the Austrian writer Robert Musil, considered by many the Marcel Proust of Fin-de-Siècle Vienna, stated that Austria’s intellectuals, artists and writers found themselves on the threshold of the new century where “out of the oil-smooth spirit of the last two decades of the 19th century, …. there rose a kindling fever. Nobody knew exactly what was on the way; nobody was able to say whether it was to be a new art, a New Man, a new morality or perhaps a reshuffling of society”.

As seen in my previous Interlude articles, the Secessionist painters, writers, architects and the artists of the Wiener Werkstätte (Viennese Workshops), had already broken with the traditions of the past, but the emerging new voices, Kokoschka, Schiele and the composers of the ‘Second Viennese School’, Schönberg, Berg and Webern, would go further still. Gustav Klimt, in his paintings Music, Philosophy, Medicine and Jurisprudence, had shown the way for the young generation into new worlds of psychological experience, using classical Greek symbols, but in subversive fashion.

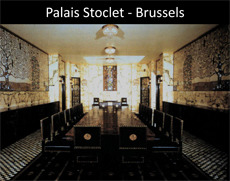

The painter, Oskar Kokoschka, came to prominence in the Kunstschau (Art Exhibition) in Vienna, in 1908. The theme of the show was the unity of house and garden, with beautifully coordinated contributions of furniture, ceramics, silverware, etc., by all of the artists of the Wiener Werkstätte. These artists, inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement in England (minus the socialism) turned from the Secessionist to a more neo-classical, art deco inspired art form, where fine art and applied art were seen as one and the same.

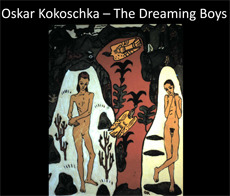

Kokoschka’s contribution was a poetic illustrated fairy tale ‘Die Träumenden Knaben’ (The Dreaming Boys). Kokoschka had been educated at the Arts and Crafts School in Vienna, where one of the subjects being taught focused on ‘The Art of the Child’, encouraging free creative activity: “The child … could show us revelations of elemental creative powers, ur-primitive art, on a new terrain in our homeland” (pp. 327/328, C. Schorske, Fin-de-Siècle Vienna). In his lithographs, Kokoschka presented his fairy tale as if set in a Persian garden, using primary colors, flat figures, devoid of traditional perspective. All of the elements seem to rise above one another on the surface of the paper. The story, however, was not just a fairy tale of a childlike world, but beneath the conventional story lay Kokoschka’s own tormented experience of puberty and sexual awakening.

Schubert

Heidenroslein, Op. 3, No. 3, D. 257

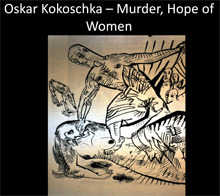

The accompanying text to Kokoschka’s lithographs imitated one of Goethe’s poems, set to music by Schubert ‘Sah ein Knab ein Röslein stehn’, but here as well, the song and text become subversive – the text has no punctuation, no capitalization of nouns, violent imagery, a frenetic rhythm; e.g., instead of ‘Röslein rot, Röslein rot’ (red roses, red roses) – we have ‘Small fish red, small fish red – I will tear you apart with my fingers until you are dead’. Kokoschka was considered ‘the wild man’ in the beautifully organized garden and house of the Kunstschau, particularly with his so-called comedy ‘Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen’ (Murder, Hope of Women), which he wrote in 1909. In the poster he shows us a ‘Pieta’, again subverting religious iconography – a woman holding a murdered man – (the red and blue colors are the traditional colors of Mary used in religious paintings since the Romanesque period). The other poster shows a man attacking a woman, the dog in the back lapping up blood; both figures show the inside of the body, muscles, veins, which are usually invisible. Kokoschka was evicted from the ‘garden’ because the bourgeois Viennese public found these violent images disturbing – like Alban Berg’s opera, ‘Wozzeck’, which deals with a similar subject matter.

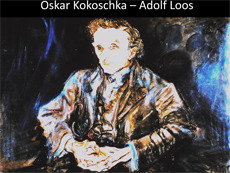

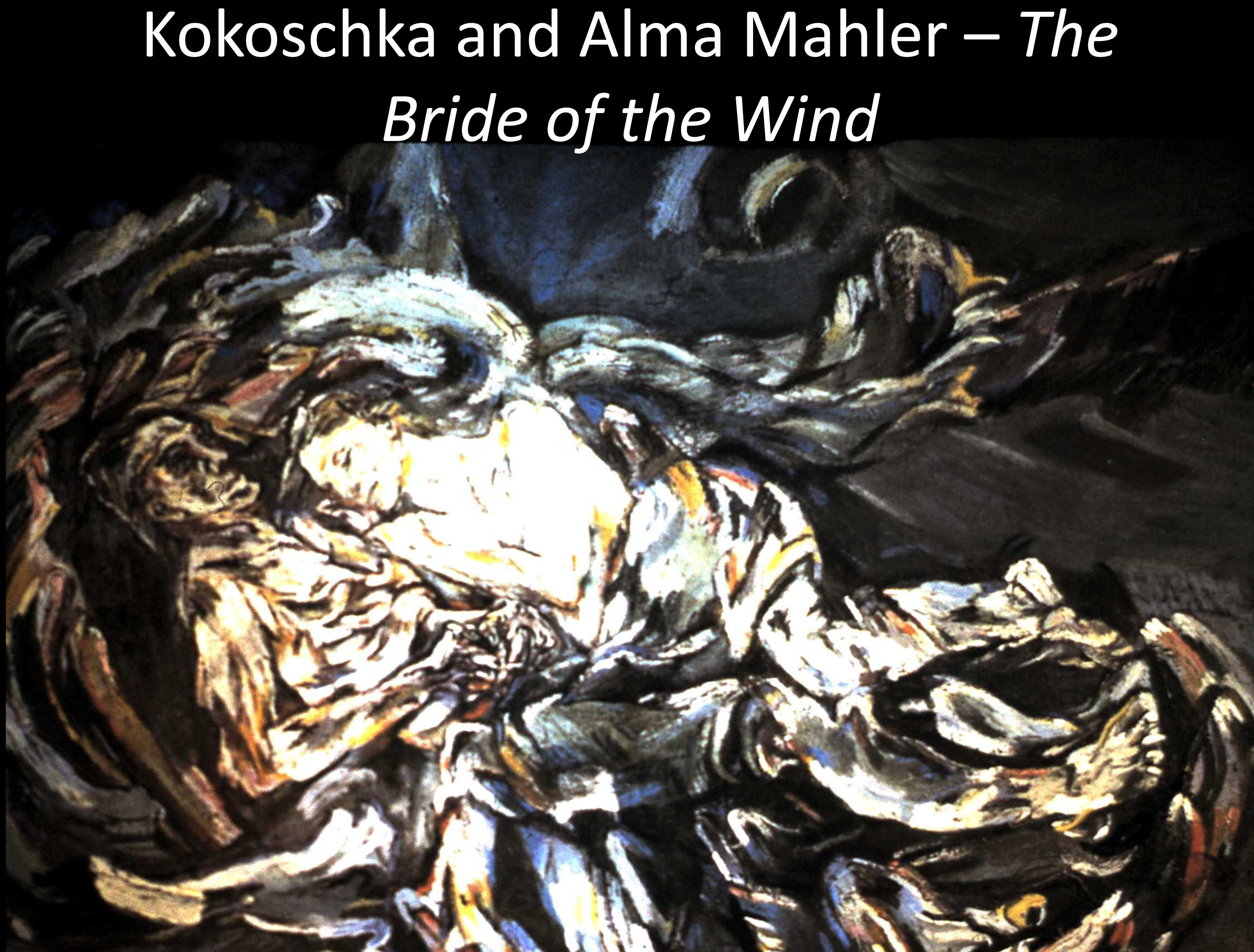

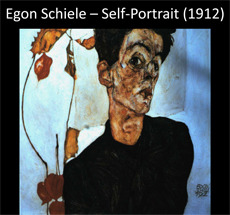

The architect Adolf Loos, took Kokoschka under his wing, and we now see a change not only in Kokoschka’s own painting style, but in what is considered the ‘expressionist’ style of this generation in art and music. Kokoschka focuses on capturing the essence of his subjects (he calls it the ‘Gesicht’, which can be translated into English not just as face, but also as vision). Here, against a diffuse background, created by powerful, visible brushstrokes, Adolf Loos is shown with his powerful hands folded, staring at the viewer. In ‘The Bride of the Wind’, Kokoschka depicts his own rigid body, with his terrified eyes staring into the surrounding nothingness of a whirlwind, with his peacefully sleeping mistress Alma Mahler at his side. Personal suffering and the projection of a troubled, divided self appear not only in his work, but also in the paintings of Egon Schiele.

Schubert

String Quartet No. 14 in D minor, D. 810, “Death and the Maiden”

In ‘Death and the Maiden’ (title taken from a Schubert quartet and song, in which a young girl pleads with death not to take her, since she is too young; and with death replying that she should not be afraid, he is a friend and in his arms she can sleep). In Schiele’s painting, death bears his own, terrified face and the young girl, looking equally anguished, embraces him.

In the music of the beginning of the 20th century, we find a similar development – also moving from a ‘Secessionist’ to an ‘expressionistic’ style, where the ‘content’ would collapse into the ‘form’.

Schönberg

Pelleas und Melisande, Op. 5

The musicians of the ‘Second Viennese School’, Schönberg, Berg and Webern, — the ‘First Viennese School’ having of course been Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven — were initially inspired by Richard Wagner and Gustav Mahler. Schönberg’s earliest compositions, ‘Verklärte Nacht’ (Transfigured Night), ‘Gurrelieder’ and ‘Pelleas and Melisande’ were heavily chromatic, in the late Romantic style of his predecessors. But soon, Schönberg, Berg and Webern moved into atonal forms of composition, away from the use of the key signature, towards what Schönberg would call “the emancipation of the dissonance”. For his composition Pierrot Lunaire, he invented the ‘Sprechstimme’, a form of vocalization between speaking and actual singing, which became the preferred form of vocal writing for these atonal, expressionist composers. From the atonal stage, Schönberg moved to a more tightly constrained form of composing with the creation of the twelve-tone system. Here, the composer typically chooses a row consisting of all twelve notes, and then builds the system in choosing the row or parts of it, either melodically or harmonically, forward, backward or inverted (i.e., Schönberg’s, Five Piano Pieces, Op.23).

Schönberg

5 Klavierstucke, Op. 23

Alban Berg

Lyric Suite

Alban Berg’s composition output is very small; he is mostly known for his two operas, ‘Wozzeck’ and ‘Lulu’, both atonal and highly expressionistic. He also uses the twelve-tone system in his Lyric Suite (considered by many as his most beautiful work) and A Chamber- and Violin Concerto, but in a lyrical and harmonic fashion reminiscent of the late romantic style of Gustav Mahler. Listeners find him therefore the most easily approachable composer of the twelve-tone style. The ‘row’ for him corresponded to actual ‘musical material’, and was not considered just as an unchanging source, but could be worked and developed just as are the varied themes and motives of a composition.

Anton Webern also followed Schönberg’s example in moving from a post-romantic period into the sparing world of atonality and twelve-tone writing. In contrast to Schönberg, however, he took the principal elements of style, the focus of the individual sounds and their brevity, to their extremes. The entire output of his work is a total of three hours of music, his symphony being 10 minutes in length, various movements lasting only less than thirty seconds each. But each separate note, dynamic and timbre become extremely important.

The three composers, like the expressionist painters, would have a profound and lasting effect on the younger generation of composers and artists in the 20th century, which we will explore in future articles.