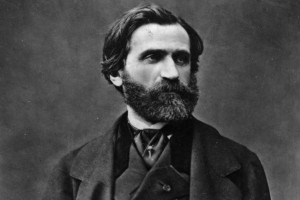

Giuseppe Verdi

Vicenzo Lavigna, Hoango, Act II: Duet: “Come potrò resistere”?

In later years, Verdi spoke rather disparagingly of his student days and of the instruction he received from Lavigna. “In the three years I spent with him, I did nothing but canons and fugues, fugues and canons, served up in every fashion. No-one taught me orchestration or how to handle dramatic music.” Yet there is evidence that Verdi was asked to “write various pieces, mostly comic, which my master made me do as exercises and which were not even scored.” In 1836, Verdi returned to Busseto to become “maestro di music,” responsible for teaching vocal and instrumental classes alongside counterpoint and composition at the music school. In addition, he conducted the concerts of the philharmonic society. As confirmed by surviving programmes of the Busseto Academie, Verdi also conducted his own compositions, among them “a capriccio for horn, a recitative and aria, an introduction, variations and coda for bassoon and a buffo duet all by Signor Maestro Verdi.” A setting of Tantum ergo for tenor and orchestra, presumably composed in 1837, has survived.

Giuseppe Verdi, Tantum Ergo

Gioachino Rossini

Gioachino Rossini, Aureliano in Palmira, Act 1, “Serena I bei rai,” “Vieni all’armi.”

Act I: Sposa del grande Osiride (All)

Act I: Ahi! L’ara si scuote (Gran Sacerdote)

Concordantly, Verdi had been working on an opera himself for almost four years. He was already 26 when his first completed opera Oberto, Conte di San Bonifacio made its debut at “La Scala” in 1839. A rudimentary plot, involving warring factions in 13th-century Italy, offers few dramatic possibilities. Yet the historical subject based on war, revolution and an arranged marriage contains many themes that Verdi would explore in later projects. In Oberto, Verdi relies principally on the conventions and format of 19th-Century Italian Opera, and contemporary voices record that the opera enjoyed “a fair success.” Bartolomeo Merelli commissioned two further operas from the composer, and the publisher Ricordi signed a contract with the composer; an arrangement that eventually made them a both a small fortune.

Giuseppe Verdi, Oberto, Act I, “Non basta una vittima”

The musical and dramatic language of Oberto, as we have seen, could not have been accomplished without the direct help from Vicenzo Lavigna, and the indirect aid from Gioachino Rossini. However, Verdi’s early operatic efforts also show the strong musical influence of Saverio Mercadante, Federico Ricci and Giovanni Pacini; more about these gentlemen in our next episode.