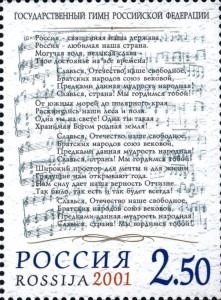

A 2001 stamp released by Russian Post with the lyrics of the new anthem

In this series, we’ll take a look at some of the world’s national anthems and see what we can learn from them. Some NAs have real titles, others just have generic titles (Hymn or National Anthem), some don’t even have words.

We’ve looked at the national anthems of France and the UK, the US and Germany, and Italy and Spain. Now we venture to Russia and China.

Russia’s Госуда́рственный гимн Росси́йской Федера́ции (Gosudarstvenný gimn Rossijskoj Federací or State Anthem of the Russian Federation) was derived from the earlier State Anthem of the Soviet Union. The original music was composed in 1944 by Alexander Alexandrov to lyrics by Gabriel El-Registan. This replaced the former use of The Internationale, the standard song of the socialist movement. The 1944 lyrics made specific mention of the leadership of Lenin and Stalin in the creation of the Soviet Union. These lyrics were dropped after 1956 because of the Stalin reference and the anthem had no words until 1977. Various attempts to find a new anthem failed and in 2001, President Putin reinstated the former Soviet anthem. A government competition resulted in newly written lyrics by Sergey Mikhalkov. His lyrics, beginning Россия – священная наша держава (Rossiya – svyashchennaya nasha derzhava; Russia – our sacred homeland) speak of the will of the people that has created this country, the second verse details the vast geographical spread of the country, and the last verse concludes with saying that ‘Our loyalty to the Fatherland gives us strength / So it was, so it is, and so it always will be!’ The chorus urges the country to be glorious and speak of the pride of the people in their country.

Putin’s re-adoption of the old Soviet hymn was not without controversy, but it provided the country with a needed focal point at a time of great change. Under Boris Yeltsin, an unpublished work by Mikhail Glinka, Патриотическая Песнь Глинки, (Patrioticheskaya Pesn’ Glinki; The Patriotic Song of Glinka) was the national anthem from 1990 – 2000.

Originally without lyrics Glinka’s manuscript, a competition found new lyrics by Viktor Radugin ‘Славься, Россия!’ (Slavsya, Rossiya!;. Be glorious, Russia).

In the end, though, the song was considered hard to remember and musically complicated. Putin’s solution of an old song with new lyrics was voted into law on 25 December 2000 and gave athletes a song with words they could sing.

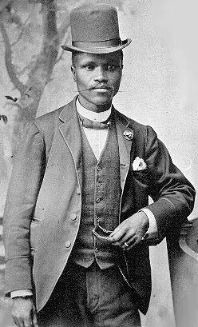

Composer Nie Er (left) and poet Tian Han (right) in Shanghai, 1933

It can be heard during the opening credits of Children of Troubled Times and served as the theme song throughout.

Children of Troubled Times poster

The songs opens with a magnificent fanfare before the first words. Those first words, 起來 (Qǐlái; Arise) are repeated later in the work three times to great effect (Qi lai! qi lai! qi lai!)

Nie Er: 義勇軍進行曲 (March of the Volunteers) (Shanghai Philharmonic Chorus; Shanghai Philharmonic Orchestra; Cao Ding, cond.)

The lyrics, as would be expected for words written during a time of civil war, urge the people who do not want to be slaves to rise and join together to ‘build our new Great Wall.’ These volunteers should march on, braving the enemies’ gunfire, with the words ‘Arise’ as their call.

The music is a march and clearly shows the influence of The Internationale, which opens with the same leap of a fourth and the same opening invocation to arise. Listen to the music after the opening fanfare (Qi lai!; Arise!) in the Chinese anthem and the opening of L’Internationale (Debout, les damnés de la terre; Stand up (or Arise), the wretched of the Earth…)

By harking back to the great socialist hymn familiar across Europe, Russia, and China, the Chinese national anthem reinforces its own message of solidarity.

Next: Australia and Ireland