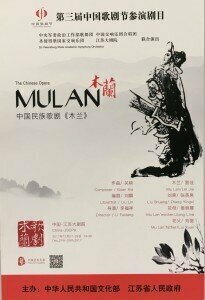

Poster showing Mulan as part of China Opera Festival programme

In early 2008, Peng made one of her final stage appearances in Mulan Psalm at the National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCPA) in Beijing. As the translator of its English libretto, I was invited to a post-performance reception held at the banquet hall on the top floor, overlooking the majestically lit Tiananmen Square and the Chang’an Avenue. We were told to submit our mobile phones and get prepared to shake hands with Her Highness. It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. One month later her husband Xi Jinping became the President of China and I never got a chance to meet her again.

Composer Guan Xia talking to production team

The trip to Nanjing was a pilgrimage then.

That’s why it took over a dozen years before the opera, always performed in a semi-staged version, to get its full production produced by JSCPA under the baton of Leif Segerstam. Sung by soprano Lei Jia and tenor Zhang Yingxi(張英席), the opera was christened Mulan(木蘭) from Mulan Psalm: It was an all too important occasion not to be missed.

Mulan

But Mulan was not alone. It was one of the over 20 opera numbers staged at JSCAP in the sheer period of one month as part of the programme of the Third China Opera Festival. A triennial event first taking place in 2011, COF is presented by the Ministry of Culture and epitomises China’s ultimate ambition for its soft power, especially on art legacy favoured personally by its highest patron. According to fellow critic Chen Zhiyin, China turns out some 20 operas commissioned by opera companies, municipalities, powerful oligarchs, and ministries every year. All traces lead to heavy government spending, which often end up in a carefully monitored success. Then most of them will be shelved and never to be performed again.

A scene of Mulan at JSPAC

And the opera canon by Chinese composers continues. It is fused by the rise in infrastructural construction where each province is building a new venue every year and each city is striving to be recognised as a City of Music by UNESCO’s Creative Cities Network, thus raising higher stakes for its leaders to get promoted.

Whether China’s dream in becoming an opera superpower will end up in an opera Bollywood is unknown and unpredictable. But an array of internationally recognised Chinese story-telling operas has received little or zero subsidy from the Chinese government: Puccini’s Turandot, Tan Dun’s Marco Polo (1996) and The First Emperor (2006), Zhou Long’s Madame White Snake (2010), Huang Ruo’s Dr. Sun Yat-Sen (2011), Christian Jost’s Red Lantern (2015), Bright Sheng’s Dream of the Red Chamber (2017), some of them never performed in China.

There is clearly a way for China to take on the world with its operas, one way or another.

Trailer of Christian Jost’s Rote Laterne (Red Lantern)