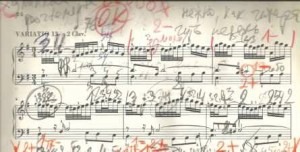

Andrei Gavrilov’s annotations on the Goldberg Variations.

Credit: practisingthepiano.com

Concert pianists will have many pieces “in the fingers” which can be downloaded and made ready for performance in a matter of days. This may include 20 or more piano concertos (I recently interviewed a concert pianist who told me he had “around 50” piano concertos in the fingers), most of Beethoven’s 32 Sonatas, many of Bach’s 48 Preludes and Fugues, plus other pieces which are ‘standard’ repertoire: Mozart and Schubert sonatas, works by Chopin, Schumann, Brahms and Liszt, much of Debussy and Ravel etc., and popular ‘standards’ from the 20th-century repertoire. Careful learning and preparation mean that repertoire can be learnt, revived and kept going simultaneously, and deep, thoughtful practise is essential for ensuring repertoire remains in the fingers (and brain) even if one is not practising it every day.

A work can never truly be considered “finished”. Often a satisfying performance of a work to which one has devoted many hours of study can be said to put the work ‘to bed’, but only for the time being. The same is true of a recording: rather than a be-all-and-end-all record, maybe a recording is better regarded as a snapshot of one’s musical and creative life at that moment. This process of “continuing” means that one performance informs another, and all one’s practising and playing is connected in one continuous stream of music-making.

Some thoughts on reviving repertoire:

• Recall what you liked about the pieces in the first place. Rekindle your affection for the pieces when you revisit them

• Don’t play through pieces at full tilt. Take time to play slowly and carefully, as if learning the piece for the first time.

• Trust your practise skills. Be alert to issues as they arise and don’t allow frustration to creep in.

• Look for new interpretative and expressive possibilities within the music. Try new interpretative angles and meaningful gestures.

• Don’t hurry to bring the piece up to full tempo too quickly. Take time to practise slowly and carefully.

• Schedule performance opportunities: there’s nothing better to motivate practise than a concert date or two in the diary.

Mozart Rondo K511

<3

Esro es muy iteresante, Estudié piano desde los 5 años… ahoraya bastabte ayor sigo ejecutando algunas partituras que recuerdoybquiero Gracias por esoo!!!!

Reinicio el contacto ( el anterior … estaba ya medio dormida… Tengo guardado unos programas de unas presentaciones que hice de niña (los buscaré) y que mantengo en mi memoria con tantísimo cariño. comencé a estudiar a los cinco años y aún hoy , ya mayor, sigo ejecutando.Amo Chopin, Bach, Tchaicovski, Lizt, y muchos , muchos más…Esta idea de recordar y recuperar aquellas partituras que tanto nos gustaban está buenísimo!!!! Y por acá termino…. sigo con ustedes… desde motevideo URUGUAY . Muchas gracias!!!!

estoy fascinada escuchando este piano que me transporta a lugares verdes naranjas y violetas

As a 75 year old amateur musician — it is very rewarding to relearn music from my youth. I can now really see What the music really “means.” So happy that now I have the time to concentrate on perfecting this music.👏👏😘