Max Bruch

Kol Nidrei, Op.47

Israel Philharmonic Orchestra / Daniel Barenboim

Jacqueline Du Pre

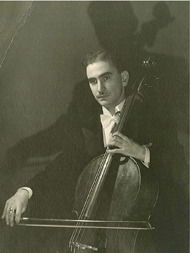

After the Second World War, my parents escaped from their native Hungary to Munich. At that time refugees had to go to Munich in order to procure documentation that allowed them to leave Europe. They did everything they could to recover from the chaos of the war. Finally, they saved enough money to purchase an Italian cello on the black market of Europe for $100 — a Vincenzo Panormo. It was an immense amount of money then. In October of 1948 they set sail for Canada somehow managing to take the cello on the ship Scythia across the ocean.

When they arrived in Halifax, Canada, the immigration officer, doubtful of my father’s stated occupation as a farmer, looked at his hands and said, “These hands have never farmed a day in your life.” My father retorted, “But I can learn!” And he did. My parents were sent to a small farming community outside of Toronto. Soon my parents heard that no one succeeds in music unless they live in Toronto. They packed their few belongings and the cello to try their luck in Toronto.

They were dismayed to learn that they would have to live in the city for two years before my dad could join the musician’s union. It seemed endless as he practiced relentlessly by day and at night he cleaned office buildings and washed cars. My mother worked in a sweatshop.

When my father finally joined the union, his first professional engagement was a radio recital invitation from the C.B.C. Tragedy struck as he exited the elevator on his way to the studio. Someone closed the heavy metal doors on the Panormo. The whole top of the cello was in splinters! My father was devastated. The repair took many months and money my parents couldn’t afford. The instrument was never the same despite good craftsmanship. Years passed before he could afford to look for another cello.

Then my dad won an audition for the Toronto Symphony. Although the TSO is one of the major orchestras of Canada, they had only a 26-week season in those days. My dad still worked at whatever he could, playing for the occasional wedding, funeral and any gig that needed a cellist. One of these started a tradition.

My father played the piece Kol Nidre by Max Bruch for the High Holy Day service of Yom Kippur — the Day of Atonement for the Jewish people. He played Kol Nidre every year for 28 years. The gorgeous work is based on the ancient chant that opens the service.

Finally my dad had the opportunity to purchase a former colleague’s cello — a Ferdinand Gagliano. It was love at first sight.

Ferdinand, 1770-1795, came from four generations of instrument makers from Naples, Italy. Alessandro, his grandfather, worked in the shops of famed luthiers Nicolo Amati and Antonio Stradivari.

The cello, a stunning amber color, has a beautiful and unusual flame on the back, harking back to the tree from which it was hewn.

The gorgeous sheen was never marred by rosin or sweat, even though my father practiced like a fiend. He lovingly wiped off the cello every few minutes with a chamois.

Austerity measures continued, until he could indulge himself with a tailpiece and tuning pegs of burnished rosewood rather than the more typical and utilitarian black ebony.

Years later, I too became a successful cellist. Following my father’s tradition, I began playing the Kol Nidre each year. Eventually, we tallied up our years of playing the piece. I had surpassed him. Between the two of us we had been playing the Kol Nidre for sixty years!

My father had always dreamed that if I sold his cello and mine, perhaps one day I could afford a Strad! By the time I was a professional, prices had skyrocketed and I would have had to sell everything I owned and the cellos.

My cello is responsive and slightly diminutive, as am I. My dad’s cello is larger and more resistant. We agreed to sell the cello to my stand partner, principal cello Anthony Ross, a very tall, athletic guy. Tony loved the cello and I played beside the instrument each day.

A few years later, Tony attracted the attention of a wealthy collector who offered Tony a valuable and historic cello to use. Cellists covet Goffriller cellos, as violinists swoon over Strads. Tony decided to sell my father’s cello through a dealer in New York and I lost track of it.

One day last fall, I got a most astonishing Facebook message. (Yes, I admit, I am an addict). The woman who had purchased my father’s cello had tracked me down. She was as anxious to hear about the cello’s history, as I was to know where the cello is now. We planned to meet when I would be in New York for a seminar in April.

It was very emotional as you can imagine. I would recognize the cello anywhere! I was able to play the cello again and I could hear my dad saying, “ Janetkém, is not these beeeaautiful?”

It was thrilling to see what good hands the instrument is in now. And the tradition? I had to shake my head in disbelief. Mairi plays for Yom Kippur at Temple Emanu-El in New York. The cello is still playing Kol Nidre!

What a wonderful moving story !…….