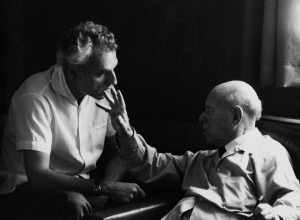

Mstislav Rostropovich

© Reuters

As with the great violinists, it is difficult to choose just ten great cellists. But as a cellist myself here are my heroes.

Pablo Casals, born on December 29, 1876 in the Catalonian region of Spain, can be credited with emancipating the cello. His revolutionary bowing technique enabled cellists to play fleeting passages with articulation, and to produce an expressive sound. Rather than the oom-pa-pa bass role it had been relegated to, the cello suddenly stepped into the limelight as a solo instrument.

One day Casals discovered crumpled, yellowing sheet music in a dusty old Barcelona bookstore that would transform music and Casals’ life. The Six Solo Cello Suites by Bach had been forgotten after they were written in 1720. Casals practiced Bach daily for the rest of his life, breathing life into these “exercises” which exemplified sanctity and spirituality.

By 1899 he was performing for royalty and embarked on an international career. He performed Don Quixote with the composer Strauss at the helm, at Carnegie Hall, in 1904.

Early in his life Casals was deeply affected by the plight of those who were oppressed. He became a fervent anti-fascist. When the Spanish Civil War broke out Casals pledged not to play in Spain until democracy was reinstated. His self-imposed exile extended to countries that recognized the regime in Spain. Out of deep admiration for President John F. Kennedy he accepted an invitation in 1961 to perform at the White House and in 1963 he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

The 200th anniversary of Bach’s death in 1950 was a turning point. Casals was persuaded to participate in a festival in Prades if all the proceeds went to a refugee hospital. The festival and the Casals Festival, which he founded in Puerto Rico, continue today.

Casals traveled widely, concertizing, giving master classes, conducting and composing. In 1971, at the age of 94, he conducted the premier of one of his final compositions the Hymn of the United Nations for an extraordinary performance at the United Nations. After the concert Casals received the U.N. Peace Medal from U Thant, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, in recognition of Casals’ stance for peace, justice and freedom. Casals was convinced that “music will save the world.”

J.S. Bach: Cello Suite No. 3 in C Major, BWV 1009: Prelude (Pablo Casals, cello)

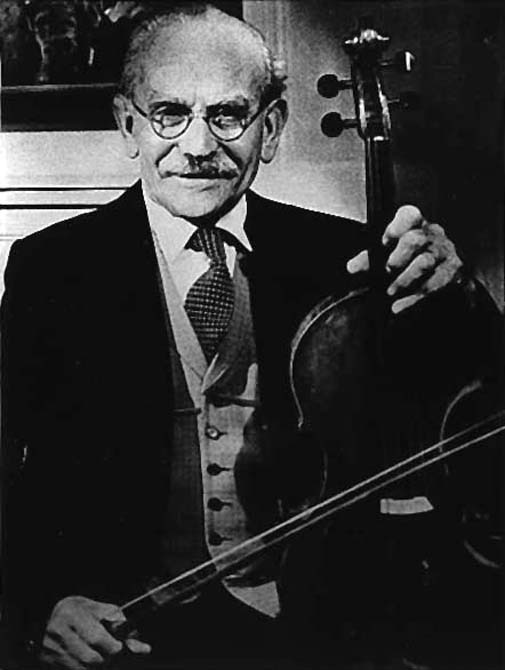

Gregor Piatigorsky

Emanuel Feuermann was born in 1902, into a musical family, in Galicia, Poland. His first lessons were on the violin but he insisted on holding it upright with an endpin. After hearing Casals at his debut in Vienna, Feuerman aspired to take cello playing to even greater heights. At the age of twelve, Feuermann made his debut with the Vienna Philharmonic playing the Haydn D Major Concerto. He became known for his regal, relaxed and upright posture, and incomparable facility. He made the upper registers sound like a dazzling coloratura soprano, re-creating the cello as Casals had before him.

By the age of sixteen he became professor at the Gurzenich Conservatoire in Cologne and later a faculty member of the Berlin Hochschule für Musik. Feuermann concertized all over Europe in the 1920’s.

His American debut in 1935 was jammed. Fellow cellists and others who attended marveled at the extraordinary cello playing. Both Pablo Casals and János Starker became great admirers.

The rise of the Nazi party necessitated a move to Zurich. Nonetheless Feuermann continued to concertize and teach in Berlin and Austria. Eventually he was trapped when the Nazi’s invaded. Feuermann was one of the musicians violinist Bronislaw Huberman managed to smuggle into Palestine and safety.

Feuermann settled in New York. He supported many contemporary composers including his friend Paul Hindemith who wrote two trios, a string duo, and a cello concerto for him. Feuermann taught at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia during the season and gave master classes in Los Angeles in the summer. Thus began a historic collaboration with Jascha Heifetz with whom he recorded the Brahms Double Concerto, performed and recorded chamber music with the violist Primrose and trios with Rubenstein. Their intention was to record all the piano trio literature.

Following a minor operation, Emanuel Feuermann died unexpectedly in 1942 at the age of 39. The most notable musicians of the day mourned his premature passing.

Feuerman plays Dvorak’s Rondo Op. 94 and Popper’s Spinning Song, with Theodore Saidenberg at the piano.

Jacqueline du Pré tragically struck down by multiple sclerosis at age 42, was another legendary cellist the world lost too early. Her meteoric career, which lasted only a decade, still resonates. Her uninhibited enthusiasm, ravishing sound, deeply expressive playing and riveting personality is permanently embedded in the hearts of fans of the cello.

She achieved rock star status after her Wigmore Hall concert in London in 1961, at the age of 16. Her performance the following year of the Elgar Cello Concerto in Royal Festival Hall revealed her uncanny ability to intensely engage her audiences. The BBC asked her to record every concerto she knew. Reviewers marveled at her extraordinary affinity for the deeply nostalgic, romantic Elgar Concerto—her signature piece. Then she met and married Daniel Barenboim. The celebrity couple recorded the Haydn C major and Boccherini Cello Concertos and performed the major sonatas for cello and piano. Her playing had been powerful, then suddenly, at the age of 26, she could no longer feel her fingers. Devastated by her diagnosis, relegated to a wheel chair, she remained devoted to teaching until her death.

Her cello mentors include William Pleeth and later Tortelier, Casals and Rostropovich. To commemorate the 50th anniversary of her London debut EMI released a 17-CD set of her recordings. Almost 30 years after her death she continues to inspire a new generation of cellists.

Edward Elgar: Cello Concerto in E Minor, Op. 85 : Adagio (Jacqueline Du Pré, cello; London Symphony Orchestra; John Barbirolli, cond.)

Paul Tortelier and Pablo Marlboro

Pierre Fournier, the son of an army general, was born in Paris in 1906. After an attack of polio he switched from piano lessons to the cello. Known for his beautiful bowing technique, remarkable finesse and poised playing, he had a varied and large repertoire—all the standard works, pieces by Debussy, Hindemith and Prokofiev, and works written for him including by Bohuslav Martinů, Jean Martinon, Frank Martin, and François Poulenc.

Fournier was an avid chamber musician. He played in the first performance of Fauré‘s String Quartet in 1925, and after Casals retired, he became the cellist of the famous trio with Jacques Thibaut and Alfred Cortot. Fournier recorded nearly all of the piano quartet chamber music of Brahms and Schubert with Artur Schnabel, Szigeti and Primrose.

Fournier became the director of cello studies at the Ecole Normal from 1937 to 1939 and taught at the Paris Conservatoire from 1941 and he became internationally treasured for his artistic depth, vibrant sound, eloquent phrasing and clarity of interpretation.

The following story confirms that cellists are a genial bunch. Fournier, after attending a concert given by Paul Tortelier said, “Paul, I wish I had your left hand,” to which Tortelier answered, “And I Pierre, wish I had your right hand.”

Francis Poulenc: Cello Sonata, FP 143 : Allegro Tempo di marcia (Pierre Fournier, cello; Jacques Fevrier, piano)

Paul Tortelier, was also born in Paris, in 1914, just months before the outbreak of the war. He won first prize at the Paris Conservatory at the age of 16 and made his debut one year later.

His ardent playing and his steadfast commitment to co-existence made an indelible impact. In 1935 he became the Monte-Carlo Orchestra’s principal cellist and two years later played Don Quixote under Strauss’s direction. That year he joined the Boston Symphony at the invitation of conductor Serge Koussevitzky making his American debut in a Town Hall recital in 1938 with the pianist Leonard Shure.

Despite his staunch resistance to Nazi ideology he returned to France, temporarily halting his career. After the war his rendition of Don Quixote for a Richard Strauss festival in London, Sir Thomas Beecham conducting, led to an invitation from Casals to be the principal cello of the Prades Festival Orchestra in 1950.

Tortelier became professor at the Paris Conservatoire and the Folkwang Hochschule in Essen, Germany. He presented master classes worldwide including in China. His notable pupils include Jacqueline du Pré and Arto Noras and his book How I Play, How I Teach, became the definitive text for cello teaching.

Tortelier began conducting and composing although his cello works and a set of variations for cello and orchestra ‘May Music Save Peace’ are not widely performed.

During the Viet Nam war Mr. Tortelier disagreed with the American stance. He refused to perform in the U.S. until 1989 after an absence of 35 years. During the 1970s, he gave a series of master classes, which were recorded and broadcast by the BBC. They illuminate his vibrant, animated spirit and captivating playing.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Cello Sonata No. 5 in D Major, Op. 102, No. 2 – I. Allegro con brio (Paul Tortelier, cello; Lothar Broddack, piano)

Gregor Piatigorsky, was born on April 17, 1903 in Ekaterinoslav, Ukraine. He began the cello at the age of seven. The family was so poor that while he studied at the Moscow Conservatory on a full scholarship, he had to play in brothels, cafés, and silent movie houses, to support his family at age thirteen. Two years later he won a position as principal cellist of the Bolshoi Theater.

Like many Russian artists during that era he was not allowed to leave the country. Piatigorsky fled to Poland on a cattle train. The authorities were in hot pursuit. He managed to cross the border unscathed but his cello was crushed. (Piatigorsky, an imaginative raconteur, relates other anecdotes, some hilarious, in his book The Cellist.)

Piatigorsky travelled to Germany where he studied with the eminent cellist Julius Klengel. Following his studies in Leipzig, Piatigorsky moved to Berlin. While there he premiered Pierrot Lunaire by Arnold Schönberg with pianist Artur Schnabel, violist/violinist Boris Kroyt, and other luminaries, which led to an invitation to audition for conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler who immediately engaged Piatigorsky as the principal cellist of the Berlin Philharmonic.

Throughout his time as an orchestral musician Piatigorsky performed as soloist and recitalist. He played chamber music with violinist Carl Flesch and Artur Schnabel and he toured with violinist Nathan Milstein and pianist Vladimir Horowitz. In 1929 when he was 26 years old the cello was still not considered a solo instrument but Piatigorsky, the handsome gentle giant, was in demand for his glorious opulent sound, animated playing and aristocratic bearing, demonstrating the cello’s rich palette of expression.

He made debuts with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Stowkowski, and with Mengelberg and the New York Philharmonic. Composers began writing for him including Prokofiev, Hindemith, and Walton. Piatigorsky collaborated with Stravinsky on a transcription of the Pulchinella Suite— the popular Suite Italienne for cello and piano.

Piatigorsky became the head of the cello department at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, from 1941 to 1949 and Boston University, 1957 to 1962, and later at the University of Southern California until his death in 1976.

During the latter part of his career, his fabulous performances with Jascha Heifetz and Artur Rubenstein, led them to be called the “million dollar trio”.

Due to Piatigorsky’s efforts to significantly expand the cello repertoire by transcribing, arranging, composing and commissioning cello pieces, the exquisite voice of the cello was popularized.

Richard Strauss: Don Quixote, Op. 35, TrV 184 : Finale (Richard Burgin, violin; Joseph de Pasquale, viola; Gregor Piatigorsky, cello; Boston Symphony Orchestra; Charles Munch, cond.)

Gregor Piatigorsky plays Rubinstein-Romance

Zara Nelsova

Zara Nelsova was born in 1917 in Winnipeg, Canada to an impoverished family who had emigrated from Russia. Her father, a flutist, put an endpin into a viola so his exceptionally talented daughter could begin cello lessons. She practiced until her fingers bled. Zara made her solo debut at the age of twelve with the London Symphony Orchestra under Sir Malcolm Sargent. Subsequently she began her studies with cello heroes, Gregor Piatigorsky, Emmanuel Feuerman and later Pablo Casals.

Zara Nelsova was the first North American soloist to tour the Soviet Union in 1966. Her superbly rich tone and heart-rending, dramatic playing led Samuel Barber to choose her to record his Cello Concerto and Ernest Bloch sought her out for Schelomo.

She often gave recitals of unaccompanied cello works of Bach, Reger and Kodály, and it was she who asked Bloch for a solo suite. He complied and wrote three for her.

Nelsova performed Sir William Walton’s Cello Concerto under the baton of the composer and was an early advocate for the Elgar Cello Concerto before Jacqueline du Pré made it her signature work. In 1969 Zara gave the first performance of Hugh Wood’s concerto, with Colin Davis conducting later performing the concerto throughout Europe on tour with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Pierre Boulez.

Zara became associated with performances of deeply romantic works by Rachmaninoff, Dvořák, Lalo and Bloch, playing all over the world, unusual in those days for a woman.

Her teaching at Juilliard 1985 to 2002 and at the Aspen School included entertaining presentations on stage deportment and style. Zara always made an entrance in her colorful gowns belled out with crinolines and a matching handkerchief as a duchess might.

Ernest Bloch: Schelomo (Zara Nelsova, cello; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Ernest Ansermet, cond.)

János Starker, one of the world’s most renowned cellists of our time often said, “I was born to be a teacher.” After decades as distinguished professor at Indiana University, he influenced generations of cellists who have followed in his footsteps. His students, prominent in every country around the globe, continue his precepts not only of the art of cello playing but also about the importance of music to humanity.

Starker by age seven was a performing and teaching child prodigy. Starker began his career as a soloist in Europe. World War II intervened. Fortuitously he survived working temporarily as a miner and electrician. He made his way to Paris in 1947 where he won the Grand Prix du Disque for his first recording of the Kodály Sonata, the “unplayably difficult” work for which he became the unsurpassed interpreter.

When he came to America in 1948 at the behest of Antal Dorati, Starker had to reestablish his career with stints as the principal cello of the Dallas Symphony, Chicago Symphony and the Metropolitan Opera. The exposure to extensive repertory infused him with expansive musical concepts. As soloist he championed works of Kodály and Bartok, all the standard repertoire, and works written for him by David Baker, Antal Dorati, Bernard Heiden, Jean Martinon, and Miklos Rozsa. His love of chamber music led him to recital and chamber music performances on every continent and concertos with nearly all the world’s major orchestras.

Known for his supreme devotion to music, his purity of tone, flawless technique and masterful interpretations demonstrated both unlimited technical and musical possibilities. He was vehemently opposed to theatrics in performing, and he resisted the cult of the personality famously saying, “I am not an actor, I’m a musician.” His over 160 recordings attest to his high standards.

Janos Starker Kodály Cello Solo Sonata III. Mvt

Mstislav Rostropovich, peace activist, humanitarian, and dissident was a larger-than-life figure during the 20th century. A burly extrovert, his playing was passionate and his mesmerizing personality and dazzling tone communicated deeply.

He was a staunch defender of human rights defying the Russian authorities when he offered asylum to the great writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. His outspoken stance on artistic freedom is evident in the iconic photograph taken at the foot of the Berlin wall. He played Bach as the wall was being torn down.

Prokofiev and Shostakovich were his mentors and they both wrote concertos for him, as did Walton, Dmitri Kabalevsky, Nikolai Miaskovsky, Alfred Schnittke, Arvo Pärt, Krzysztof Penderecki, Lukas Foss, and Benjamin Britten, which Rostropovich premiered.

In 1987, the year he celebrated turning 60, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, performed fifteen concertos, conducted several symphonies, and performed all six Solo Cello Bach Suites in five concerts with three different orchestras!

Compelled by the immense and varied orchestral repertoire, he became a conductor; eventually of the National Symphony from 1977 to 1994 premiering over 50 works.

With his wife he formed The Rostropovich-Vishnevskaya Foundation, which “promotes the health and wellbeing of children in need” through public health programs around the world. To date they have provided life-sustaining health programs to 20 million children.

Dmitry Shostakovich: Cello Concerto No. 1 in E-Flat Major, Op. 107 – I. Allegretto (Mstislav Rostropovich, cello; Hugh Seenan, horn; London Symphony Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

Yo Yo Ma needs little introduction. He is not only an eclectic and versatile artist but a well-known spokesman and statesman for the arts. His collaborations with a broad range of performers across all genres of music have extended the musical frontier. Yo Yo more than anyone has paved the way for music to become a conduit of cross-cultural communication and interaction.

Born in Paris 1955 of Chinese parents he studied at New York’s Juilliard School and Harvard University, performing from the age of five. Since then he has appeared as one of the most in-demand of soloists. He has received eighteen Grammy Awards.

Ma has performed the standard classical repertoire, and bluegrass, Chinese, Tango, Brazilian and jazz music. Yo Yo has done it all—from appearing on Sesame Street to the Late Show with Stephen Colbert and for countless important milestones—in 1986, he was soloist with the New York Philharmonic during their 100th anniversary tribute to the Statue of Liberty; he performed at the 2009 inauguration for President Obama with violinist Itzhak Perlman, pianist Gabriela Montero and clarinetist Anthony McGill; he performed at the funeral mass for Senator Edward Kennedy, and for the service to honor victims of the Boston Marathon bombings.

Yo Yo’s Silk Road Ensemble has traveled the world and excited audiences with their stellar performances, unusual instrumentation and expansive arrangements of world music. Their film, The Music of Strangers: Yo-Yo Ma and Silk Road Ensemble is receiving extremely positive reviews.

Since 2006 Yo Yo Ma has been a United Nations Messenger of Peace. In 2001 he was awarded the National Medal of Arts and in 2011 the Presidential Medal of Freedom. We can only marvel at his winning smile, generosity of spirit and gorgeous, effortless playing, and wonder what he might do next. He says it best:

“As musicians, we transcend technique in order to seek out the truths in our world in a way that gives meaning and sustenance to individuals and communities. That’s art for life’s sake.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104, B. 191: Allegro (Yo-Yo Ma, cello; New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Kurt Masur, cond.)

Silk Road Project: Arabian Waltz

Paul Tortelier played a concert in Tampa in late 1983 early 1984 in the McKay Auditorium at the University of Tampa. The first time I saw him and his famous bent End Pin named after him. I even have Newspaper Articles announcing it.

Why is there no mention of Marc Coppey?

I was expecting Mischa Meisky to be on the list..Wonder why he isn’t.

Meisky is ok, others are better, for example Steven Isserlis!

I had the great pleasure of listening to Mr Yo Yo Ma perform at the Teatro Colon, after it’s full restoration. It was so emotional to me to find out the acoustic was intact, altogether with the privilege of being so close to such a magnificent artist.