Hogarth: A Rake’s Progress No. 1

We can see from the very first painting, that the road to ruin is ahead of him – he is shown in the act of abandoning his pregnant fiancée, Sarah Young, while being measured for his new clothes. The house is in chaos, but he’s off to the big city.

Hogarth: A Rake’s Progress No. 2

By the last picture, insane and violent, he’s in Bethlehem Hospital, better known as the mental asylum Bedlam. The only to offer succor to him is his Sarah Young, who he spurned so carelessly in the first picture.

Hogarth: A Rake’s Progress No. 8

Stravinsky had seen A Rake’s Progress in 1947 in Chicago and, along with librettists W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman, created a modern opera on an eighteenth-century topic. In order to create a better story line, the road to ruin for Tom Rakewell is opened by his great new friend, Nick Shadow, who, in the end, turns out to be the Devil, turning it into a Faust story.

As Tom wishes he were better placed, he speaks to his fiancée, now named Anne Trulove, and resolves to “live by my wits and trust to my luck.”

Stravinsky: A Rake’s Progress: Act I Scene 1: Aria: Since it is not by merit… (Tom) (Jon Garrison, Tom Rakewell; Orchestra of St. Luke’s; Robert Craft, Conductor)

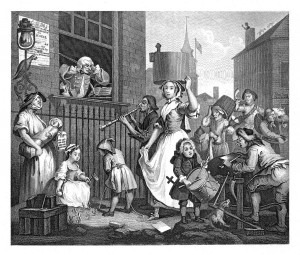

Nick Shadow appears and tells him that a (previously unknown) rich uncle has left him a fortune – he’s a rich man! Everyone agrees that he should go to the city to settle this fortunate estate. We know from Hogarth’s pictures that Tom has few wits and worse luck, so he scarcely has the best preparation for his launch into high society in London.

The second act sees Tom in the city, angrily slamming the window against the noise in the street, which might be taken as a sly reference to Hogarth’s own engraving on noise, The Enraged Musician.

Hogarth: The Enraged Musician

The opera ends with Nick Shadow playing a cheating card game with Tom for his soul.

Stravinsky: A Rake’s Progress: Act III Scene 2: Duet: Well, then. My heart is wild with fear… (Nick, Tom, Anne) (John Cheek, Nick Shadow; Jon Garrison, Tom Rakewell; Jayne West, Anne Trueheart; Orchestra of St. Luke’s; Robert Craft, Conductor)

When Tom manages to win, Nick rewards him by making him go insane. As he sits in Bedlam, he believes he is now Adonis, awaiting the arrival of his Venus. When Anne arrives, he won’t recognize her until she admits she is Venus. He falls asleep and she leaves. When he awakes and she is not there, he rages and then dies from his madness.

Stravinsky: A Rake’s Progress: Act III Scene 3: Finale: Where art thou, Venus? (Tom, Chorus) (Jon Garrison, Tom Rakewell; Gregg Smith Singers; Orchestra of St. Luke’s; Robert Craft, Conductor)

After his death, the main characters return to the stage, including Tom (the men without their 18th century wigs) and give us the moral: “For idle hands and hearts and minds, The Devil finds work to do…”

Stravinsky has changed Hogarth’s commentary on society into a more classical story, as the eight original pictures were quite difficult to translate into a three-act opera, and, in the end, has created something with greater resonance for his 20th-century audience.