Médée 2019: Elena Stikhina (Médée)

© SF/Thomas Aurin

Luigi Cherubini’s Medea is nothing if not firmly and consistently associated with Maria Callas. The Greek American soprano revived this masterpiece from relative obscurity, and committed it to stage, disc, film, but most importantly to legend. Any Medea needs to accept comparison with Callas’ unforgettable turn at this tragic heroine who commits the unthinkable by murdering her own children out of revenge for Jason’s abandonment.

Médée 2019: Pavel Černoch (Jason), Rosa Feola (Dircé)

© SF/Thomas Aurin

Salzburg Festival’s 2019 Médée, performed in its original French version, failed on many accounts; but it certainly pushed boundaries in terms of stage set and direction. The Australian-Swiss Director Simon Stone gives the classic Euripides story a contemporary and intellectually startling repositioning, focusing on the experience of an immigrant’s isolation and social exclusion. Thwarted and rejected by the father of her children, the exiled Médée is slowly driven to total despair. It is a far more thoughtful and relevant interpretation than the more common portrayal of an out of control and vindictive witch.

The sumptuous and hyper realistic stage sets (Bob Cousins) situate the story in contemporary Salzburg – an unabashedly pandering nod to the audience – while the exiled Médée struggles to stay in touch from an internet café in Tbilisi (Colchis is reputedly in today’s Georgia). Frequent and often heavy-handed videography (by the director himself) relentlessly drives home the plot. SMS correspondence is read out and projected on the screen, replacing the traditional spoken dialogue and recitatives.

Médée 2019: Alisa Kolosova (Néris)

© SF/Thomas Aurin

The highly stylized interiors of the stage sets were utterly Instagramable, awesomely detailed and occasionally brilliant. A wedding dress store opens the opera and cleverly sets the scene for preparations of the fateful wedding between Jason (of the Argonauts) and Dircé (daughter of King Créon of Corinth).

Médée’s arrival in Corinth takes place in a visually astounding double decker set. The upper half features the arrivals area at Salzburg airport, where Créon, here as a government minister rather than a king, and his forces refuse Médée entry in a nowadays rather typical illegal immigrant scene. The scene is documented live on a massive TV screen in Jason and Dircé’s lush apartment below, where Néris (Médée’s slave in the original, now a nanny of sorts) and the children are going about their lives in a fully furnished apartment featuring full kitchen, living- and bedrooms worthy of an Elle Décor spread. A clever idea showing how news comes into people’s homes and lives, and affects them.

Médée 2019: Vitalij Kowaljow (Créon)

© SF/Thomas Aurin

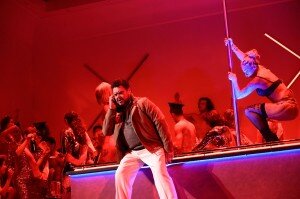

The third act features Médée entering the wedding banquet disguised as a waitress (after dispatching a real waitress in the venue’s toilet in true Hollywood style), and wreaking havoc on the wedding by knifing both Dircé and Créon (no poisoned dress here).

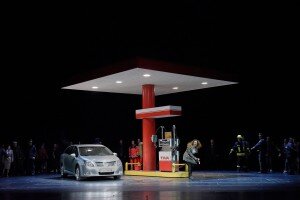

Médée takes the children and takes them on a harrowing car ride outside Salzburg – nerve-wrackingly but also irritatingly portrayed in a video during the Third Act Intermezzo (one of the most arresting orchestral pieces of the opera), until Médée ends up at a remote gas station where she tranquilizes her children and then sets herself and the car on fire while a distraught Jason, Néris, the police and firefighters close in.

Highly dramatic and unforgettable scenes, with some working better than others. The visuals clearly dominated. Alas, the musical quality fell short of Festival standards.

Médée 2019: Marie-Andrée Bouchard-Lesieur (Deuxième Femme), Rosa Feola (Dircé) und Tamara Bounazou (Première Femme)

© SF/Thomas Aurin

The many weaknesses in Cherubini’s opera scream for a true prima donna to take the helm. Salzburg had planned to cast Sonya Yonsheva in the gruelling title role, but her pregnancy got in the way and she was replaced by Elena Stikhina.

The 32 year old Russian soprano had been announced with a fair bit of fanfare after some enthusiastically reviewed performances on major stages. But she failed to truly deliver what this role needed. Her voice doesn’t possess the sparkle and blading attack in the heights, and it lacks the depth that this role demands.

Médée 2019: Elena Stikhina (Médée)

© SF/Thomas Aurin

Her final scene, a highlight of operatic literature, was visually arresting but emotionally empty. Stone did Stikhina no favours by abandoning her on the large stage with little more than a car and gas station. Even a Caballe would have struggled to command emotional attention in such a setting. The Russian soprano, giving her Salzburg debut, certainly gave it her passionate best and she’s a fine and attractive actor.

Médée’s former partner Jason and the father of her children was played by Czech tenor Pavel Černoch. While he occasionally produced some gorgeous middle register tones, particularly while singing offstage, his voice is too small, too unmodulated and too bland to matter. His heights are uncomfortably strangled and there was no vocal or physical chemistry between Médée and her former lover. But he looks great in videos.

Médée 2019: Elena Stikhina (Médée), Ensemble

© SF/Thomas Aurin

Dircé was sung by young Italian soprano Rosa Feola, who was accurate and proficient and a talented actress. But her finest vocal moments were stolen by the distracting, annoying and vertigo-inducing videography as a backdrop to her main first act aria.

Vitalij Kowaljow sang precisely, but lacked the gravitas for Créon. He resembled a second-tier oligarch, rather than an important king.

The Vienna Philharmonic, one of the world’s finest orchestras, were led by Thomas Hengelbrock. They sounded like they hadn’t quite decided whether Cherubini should be played like Beethoven, Mozart or Gluck. One German critic concluded that they made the score sound like “hysterical Haydn”.

For all its visual splendour, the stage was perhaps the biggest problem. The organizers chose to produce this in the cavernous Grosses Festspielhaus, whereas this sort of opera

would be far better suited for a smaller and intimate stage like the Haus für Mozart. But perhaps the Festival needed to sell more tickets.

Performance attended: 30 July 2019