Musical organ clock

In a previous episode on the “Mechanical Mozart” I have introduced you to the mechanical instrument, most commonly associated with a clock, that plays music at regular time intervals. Unlike a conventional chiming clock, this device plays music selected automatically or manually from a repertory encoded on a variety of different mediums. In the 18th century the manufacture of “Clarion clocks,” instruments that produced music by bells made of glass or metal, was concentrated in London. The Viennese variety was called “Flötenuhr,” idiomatically translated as “mechanical organ” as it produced sound by the use of wooden or metal pipes. Over a period of about 100 years, ranging from about 1720 to 1820, the instrument underwent dramatic improvements and happily played arrangements of overtures, arias, selected parts of flute concertos and sonatas, marches, and dance music. You already know that Mozart composed dedicated works for that instrument, but you might be surprised that even the mighty Ludwig van Beethoven got into the act.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Allegro for mechanical Clock, WoO 33, Nr. 3 (arr. organ)

Beethoven’s Ear trumpet

The “Flötenuhr” of the 18th and 19th centuries commonly consisted of one or two small ranks of four-or two-foot pipes. A rotating wooden barrel featuring raised stubby wooden pegs driven by gravity on a series of weights sounded the pipes. Following Beethoven’s death, the auction catalog listed under item 184, “Clavierstücke mit Begleitung, zum Teil unbekannt” (Piano pieces with accompaniment, partly unknown.) The known compositions are a set of four-hand piano variations composed for Josephine and Therese Brunsvik in 1799. Josephine married count Joseph Deym von Střítež, the owner of the famous Viennese art gallery. And it was for his collection of “Flötenuhren” that Mozart had written his “mechanical” compositions. We know that Beethoven owned copies of 2 of Mozart’s “Flötenuhr” compositions, obtained from Deym to use as patterns for similar pieces. When Beethoven presented Deym with 3 works for mechanical clock, he also included the set of four-hand piano variations for his future wife and sister in law. Since none of Deym’s mechanical clocks have survived the ravages of time, we don’t really know if the Beethoven pieces were ever played on that instrument. However, since the organ is probably the instrument most capable of approaching the effects produced by a Flötenuhr, these works were finally published in 1962 for that particular instrument.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Allegro for mechanical Clock, WoO 33, Nr. 1 (arr. organ)

Mälzel

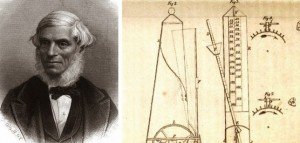

Besides the “Flötenuhr,” Beethoven was also fascinated by another mechanical device; the metronome! Invented by the Dutch mechanic Dietrich Nikolaus Winkel around 1800, the construction was copied by Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, who registered a patent. The matter was taken to court and Winkel won, however Mälzel’s name had already inseparably become associated with the metronome. Beethoven personally knew Mälzel, as he had previously asked him to construct a hearing aid! Since Beethoven had regarded traditional tempo indications as insufficient, he greeted the arrival of the metronome with great enthusiasm. “I have long been thinking of abandoning these nonsensical terms allegro, andante, adagio, presto,” writes Beethoven, “and Mälzel’s metronome gives us the best opportunity to do so. I give you my word here and now that I will never use them again in any of my new compositions.” True to his word, he published metronome marking for all of his symphonies, first eleven string quartets and a number of other pieces. Although he did not provide metronome markings for the late string quartets, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that he intended to. While the subject of tempi in Beethoven’s compositions remains a thorny issue, it is said that the “Allegretto scherzando,” the second movement from his Eighth Symphony, is an affectionate parody of the metronome. You see, Beethoven and Mälzel had a falling out over performance rights for Wellington’s Victory. Beethoven filed a legal complaint, but in the end they reached a compromise and reconciled. As such, it is at least conceivable that Beethoven wrote this movement to patch up their friendship, specifically since it also includes a little tune originally written as a canon to the text “Ta-Ta-Ta, Lieber Mälzel.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No 8, “Allegretto scherzando”