“Giant in the Shadows”

100 years ago, Max Reger (1873-1916), one of the giants of music in Germany passed away prematurely at age 43. He was an exact contemporary of Rachmaninoff, one year younger than Scriabin, and one year older than Schoenberg and Ives. Initially, Reger rose to striking prominence within the musical world, and he was widely regarded by many as the best hope for the future of music. Significantly, Reger worked during a breathless time of history, with rapid urbanization, social upheavals, and a burgeoning industrial sector calling into question the old socio-political orders of Europe. And Reger responded with an unprecedented work ethic that produced an astonishingly large number of compositions. “I sit 20,000 miles deep in work,” he once remarked, and during his short life he artistically explored very major genre except opera. Although respected by Arnold Schoenberg and other modernists, he was savagely criticized for music that was difficult to categorize and label. And in the annals of music history, he undeservedly has become a mere footnote.

100 years ago, Max Reger (1873-1916), one of the giants of music in Germany passed away prematurely at age 43. He was an exact contemporary of Rachmaninoff, one year younger than Scriabin, and one year older than Schoenberg and Ives. Initially, Reger rose to striking prominence within the musical world, and he was widely regarded by many as the best hope for the future of music. Significantly, Reger worked during a breathless time of history, with rapid urbanization, social upheavals, and a burgeoning industrial sector calling into question the old socio-political orders of Europe. And Reger responded with an unprecedented work ethic that produced an astonishingly large number of compositions. “I sit 20,000 miles deep in work,” he once remarked, and during his short life he artistically explored very major genre except opera. Although respected by Arnold Schoenberg and other modernists, he was savagely criticized for music that was difficult to categorize and label. And in the annals of music history, he undeservedly has become a mere footnote.

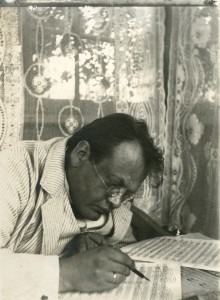

Reger was born in the small Bavarian town of Brand, but grew up in the city of Weiden. He studied organ, piano and violin with his parents, and his friendships with Eugen d’Albert and Feruccio Busoni gave rise to a number of early piano compositions. Eventually, the preeminent theorist Hugo Riemann accepted him as a composition student, and introduced the young composer to the polyphonic models of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms. His first published compositions led to faculty appointments in Wiesbaden, Munich and eventually Leipzig. Always hard working and hard living, Reger was continuously on the verge of a mental breakdown. He resigned from his post as conductor of the Meiningen Court Orchestra and settled with his family in Jena. An insane concert schedule saw him travel all over Europe, and he unexpectedly died from a heart attack at age 43. Reger’s musical legacy includes 146 opus numbers and an enormous number of un-catalogued music. It was predicted that Reger would attain musical immortality, as a textbook for that period considered him and Arnold Schoenberg the future of German music. Sadly, despite persistent advocacy by Adolf Busch, Rudolf Serking and George Szell, Reger’s music has comparatively vanished from concert and recital halls.

Max Reger: Sinfonietta Op. 90

According to Leon Botstein, “Reger found a distinct musical voice that is based on narrative spontaneity and cast in traditional genres.” This simply means that he relied on the generative principles of early romanticism practiced by Schumann and Liszt, and placed it within the formal logic we associated with music ranging from Mozart to Brahms. This idiosyncratic kind of modernism made Reger’s music highly controversial, yet highly original and immediately recognizable. Much of his music communicates a lush and luxuriant sound world built from his brilliant use of chromaticism and an advanced harmonic language. Although his music remains strictly tonal, his extremely fast modulations almost convey a sense of atonality. Reger preferred a contrapuntally dense texture, and he thus enjoys a particularly high reputation among organists. In essence, Reger’s musical style fuses the influences of Bach and Wagner into an original musical language that is forward looking, yet is also inextricably bound to the past. Botstein considers “Reger to be a great original voice from the turn of the last century, a composer whose works deserve to be returned to our concert stages, both in orchestral and chamber concerts.”

You May Also Like

- Always trust your Mother-in-Law!

Max and Elsa Reger Throughout the turbulent and highly emotional times of courtship and early marriage, Max and Elsa Reger could steadfastly rely on the support of Auguste von Bagenski, Reger’s mother in law. - Max Reger

“In music, I owe everything to J.S. Bach” Already a skilled pianist and organist, young Max Reger (1873-1916) saw performances of Meistersinger and Parsifal during his first Bayreuth pilgrimage. - A Date with “Schlamperl”

Max Reger and Elsa von Bercken Love, it is said, knows no boundaries! Too bad somebody forgot to tell the Catholic and Protestant Churches!

More Composers

-

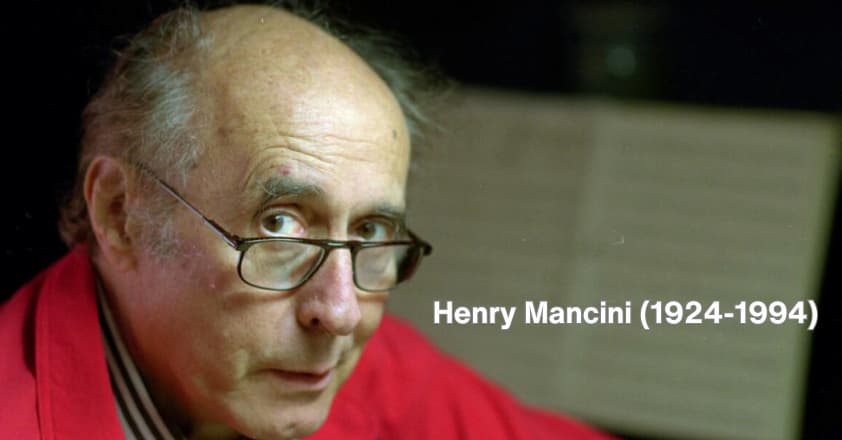

Henry Mancini “Success is not usually easy or fast”

Henry Mancini “Success is not usually easy or fast” -

Bedřich Smetana “My fatherland means more to me than anything else”

Bedřich Smetana “My fatherland means more to me than anything else” -

Georges Auric “Down with impressionism and all those beautiful sonorities”

Georges Auric “Down with impressionism and all those beautiful sonorities” -

Francis Poulenc “I simply follow my own feelings”

Francis Poulenc “I simply follow my own feelings”