Matthias Grünewald

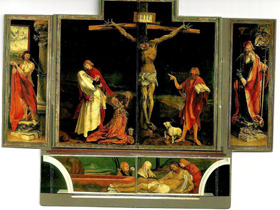

Grünewald’s altarpiece consists of a group of panels on a wooden base, designed for the church’s high altar. The altarpiece has movable wings pivoting on hinges, which allowed three successive views. In its closed position, the Isenheimer Altar’s first view shows an enormous crucifixion on the central panel, Jesus in agony on the cross, lips blue, with distorted hands and feet penetrated by enormous nails and a thorn-ridden, pain-contorted body. To the left of the cross, we see the Virgin Mary, fainted, held in the arms of John the Evangelist, and at their feet, Mary Magdalene in despair – seemingly painted out of proportion to the standing figures. The porcelain ointment jar next to her bears the date 1515, the year in which the altar was completed. To the right of the cross is St. John the Baptist with the sacrificial lamb, pointing an elongated finger towards the cross — the chalice, filling with blood, would later inspire the myth of the Holy Grail. The striking aspect of the crucifixion is the extreme suffering shown — very different from the more typical idealized Renaissance renditions at the time, and not seen again until the Baroque era in the 17th century. The left side-panel shows St. Sebastian (a possible self-portrait of the painter, Mathis), the right side- panel, St. Anthony, patron saint of the Antonite monastery in Isenheim, which had commissioned the altar. Both saints are painted in Renaissance-style settings, idealized and perfectly proportioned. The Predella shows the Lamentation and Entombment of Jesus, again with the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene and John, the Evangelist, which became the inspiration for the second movement in Hindemith’s symphony.

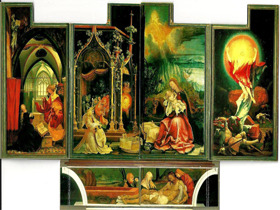

Grünewald’s altarpiece consists of a group of panels on a wooden base, designed for the church’s high altar. The altarpiece has movable wings pivoting on hinges, which allowed three successive views. In its closed position, the Isenheimer Altar’s first view shows an enormous crucifixion on the central panel, Jesus in agony on the cross, lips blue, with distorted hands and feet penetrated by enormous nails and a thorn-ridden, pain-contorted body. To the left of the cross, we see the Virgin Mary, fainted, held in the arms of John the Evangelist, and at their feet, Mary Magdalene in despair – seemingly painted out of proportion to the standing figures. The porcelain ointment jar next to her bears the date 1515, the year in which the altar was completed. To the right of the cross is St. John the Baptist with the sacrificial lamb, pointing an elongated finger towards the cross — the chalice, filling with blood, would later inspire the myth of the Holy Grail. The striking aspect of the crucifixion is the extreme suffering shown — very different from the more typical idealized Renaissance renditions at the time, and not seen again until the Baroque era in the 17th century. The left side-panel shows St. Sebastian (a possible self-portrait of the painter, Mathis), the right side- panel, St. Anthony, patron saint of the Antonite monastery in Isenheim, which had commissioned the altar. Both saints are painted in Renaissance-style settings, idealized and perfectly proportioned. The Predella shows the Lamentation and Entombment of Jesus, again with the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene and John, the Evangelist, which became the inspiration for the second movement in Hindemith’s symphony.The second view of the altarpiece was usually shown only on specific Church Holy Days. The center panel depicts The Angel Concert with angels singing and playing for the Virgin Mary and Jesus. This particular subject and its obscure meaning have made it one of the most discussed paintings in the annals of art history, as well as the inspiration for the first movement of Hindemith’s symphony. The left side-panel shows The Annunciation and the right side-panel, The Resurrection and Ascension.

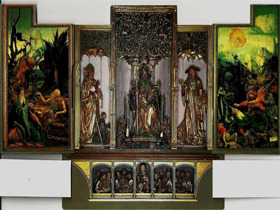

The third view of the altarpiece was seen only on January 17th, St. Anthony’s name day. In the middle, it shows the carved figure of St. Anthony, healer of the sick and protector of farm animals (alluded to by the small statues of the farmers with the rooster and pig at the Saint’s feet). St. Anthony is flanked on the right by St. Hieronymus with the lion, and on the left, by St. Augustine (354-430 C.E.), the hermit who had established the monastery rules for the Antonite Order. The small figure at St. Augustine’s feet is Johann de Orlicao, preceptor of Isenheim until 1490, who had commissioned the sculptures. The Predella now shows the carved figures of Jesus and the Twelve Apostles. All of these sculptures are the work of Nikolaus von Haguenau. Grünewald’s painting to the far right depicts The Temptation of St. Anthony, an extraordinary Bosch-like presentation of monsters and demons attacking the Saint. The painting to the far left shows St. Anthony visiting St. Paul the Hermit. Both paintings also inspired Hindemith’s compositions.

The third view of the altarpiece was seen only on January 17th, St. Anthony’s name day. In the middle, it shows the carved figure of St. Anthony, healer of the sick and protector of farm animals (alluded to by the small statues of the farmers with the rooster and pig at the Saint’s feet). St. Anthony is flanked on the right by St. Hieronymus with the lion, and on the left, by St. Augustine (354-430 C.E.), the hermit who had established the monastery rules for the Antonite Order. The small figure at St. Augustine’s feet is Johann de Orlicao, preceptor of Isenheim until 1490, who had commissioned the sculptures. The Predella now shows the carved figures of Jesus and the Twelve Apostles. All of these sculptures are the work of Nikolaus von Haguenau. Grünewald’s painting to the far right depicts The Temptation of St. Anthony, an extraordinary Bosch-like presentation of monsters and demons attacking the Saint. The painting to the far left shows St. Anthony visiting St. Paul the Hermit. Both paintings also inspired Hindemith’s compositions.Symphony, “Mathis der Maler”

Philadelphia Orchestra

Eugene Ormandy

With this masterpiece, inspired by his many travels to the Low Countries, France and Italy, Grünewald had established himself as an artist influenced both by the Northern European painting tradition, such as Van Eyck, Van der Weiden and Dürer, and by Italian masters, such as Mantegna, Raphael and Pollaiuolo. Grünewald uses symbols traditionally associated with the Old Testament, such as the prophet Isaiah in The Angel Concert, but uses an unusual setting — here a Gothic chapel with a dramatic depiction, both in form and color. In The Annunciation, the Archangel Gabriel’s outstretched, unusually elongated fingers are more demanding rather than welcoming, and the very dramatic rendering of his colorful clothes emphasizes his turbulent entrance. The bright red color and dramatic flair which Grünewald uses for the vestments carries through all of the paintings and is reminiscent of the paintings of El Greco, as are the foreshortened views in the paintings — really more reminiscent of Medieval concepts of time and space rather than the single vanishing point of Renaissance paintings.

As mentioned above, it is the center panel with The Angel Concert which first captured Hindemith’s attention and was the inspiration for his first movement. The subject itself cannot be found in the entire iconography of Northern European Painting – it may go back to the mystic tradition of the Middle Ages, such as in the visions of St. Brigitta. The depiction of angels, with one group situated in the foreground in a Gothic chapel, brightly lit, and the strange, bird-like, feathered angel, who is not looking towards the Virgin and Jesus, but rather into the dark background filled with floating creatures, is highly unusual and very mysterious. Equally unusual is the division between the dark setting of the chapel and the light-filled side of the Virgin Mary and Jesus with an almost impressionistically rendered landscape behind them. Grünewald uses the same impressionistic technique for the landscapes in both panels in the third view of the altar, which explains in part the renewed interest in his work in the 20th century.

As mentioned above, it is the center panel with The Angel Concert which first captured Hindemith’s attention and was the inspiration for his first movement. The subject itself cannot be found in the entire iconography of Northern European Painting – it may go back to the mystic tradition of the Middle Ages, such as in the visions of St. Brigitta. The depiction of angels, with one group situated in the foreground in a Gothic chapel, brightly lit, and the strange, bird-like, feathered angel, who is not looking towards the Virgin and Jesus, but rather into the dark background filled with floating creatures, is highly unusual and very mysterious. Equally unusual is the division between the dark setting of the chapel and the light-filled side of the Virgin Mary and Jesus with an almost impressionistically rendered landscape behind them. Grünewald uses the same impressionistic technique for the landscapes in both panels in the third view of the altar, which explains in part the renewed interest in his work in the 20th century.This center panel became the inspirational beginning for Hindemith’s compositions. He had initially started to work on an opera in four acts, with each act introduced by an instrumental prelude depicting one of the panels from the Isenheimer Altar. The orchestral suite, commissioned by Furtwängler, was originally conceived to consist of the four preludes. Hindemith had written two of the preludes, Engelkonzert/Concert of Angels, whose origin was the old German folksong “Es sangen drei Engel/Three angels singing” and the Grablegung/Entombment, which is the depiction in the altar’s Predella — when he ran out of ideas. With only two months before the Berlin performance, he suddenly found inspiration in the other two paintings of the altarpiece, The Temptation of St. Anthony and The Encounter of St. Anthony and the Hermit, St. Paul. The Temptation of St. Anthony became the (final) third movement of the symphony, whereas both paintings became the basis for the opera, Mathis der Maler. The symphony was successfully performed and well received in Berlin; soon thereafter, however, Hindemith’s opposition to the Nazi regime became widely known — his work was labeled “degenerate” and performance of his opera was banned. The story of the opera (Hindemith wrote the libretto himself) is set during the Reformation at the time of the Peasant’s War of 1524, during which period Mathis the Painter struggled against the suppressive rule of Catholics against the Protestants whom he supported. Mathis becomes disillusioned with the uprising, tormented like St. Anthony between responsibility and all of the human temptations of wealth, power, love. St. Anthony/Mathis is told by St. Paul the Hermit to give up all worldly pursuits and dedicate his life to art. The opera was never performed in Germany – Hindemith left for a teaching position in Turkey, and then emigrated to Switzerland and to the United States.

Like Grünewald, who moved between Medieval and Renaissance concepts, Hindemith moved from the late Romantic tradition of the 19th century to abandoning formal coherence, thematic development and tonal harmony, moving towards pulsating meters, irregular accents and dissonance, which aligned him with the composers of the 20th century, such as Bartók, Stravinsky and the early Schönberg.

Hindemith’s symphony revived a symphonic tradition with had largely been abandoned since the death of Mahler, but moving it clearly into the 20th century. Mathis der Maler, symphony and opera, are Hindemith’s credo, his mission statement – pursuing his art against all odds.