The 2010 film “Mahler on the Couch” provided a fictional reconstruction—dressed up as a grand historical drama—of the famous therapy session involving Sigmund Freud and Gustav Mahler! We do know that the meeting actually did take place, but how did it all come about? Merely one month after his daughter Maria Anna had died as the result of scarlet fever and diphtheria in the summer of 1907, Gustav Mahler was diagnosed with a potentially fatal heart condition! Deeply shaken, the composer withdrew into a world of morbid visions and deep trauma. As you might well imagine, this did not have a positive effect on his already shaky marriage. Alma Mahler writes in her diary, “Work, exaltation, self-denial and the never-ending quest were his whole life…he noticed nothing of all it cost me. He was utterly self-centered by nature…” When Alma went for a spa holiday in the summer of 1910, she met the young architect Walter Gropius, widely regarded as one of the pioneering masters of modern architecture. They quickly engaged in a passionate and all-consuming affair, and one day a love letter from Gropius ended up in Mahler’s hands. In fact, Alma accused Gropius of intentionally misaddressing the envelope in order to expose the affair and enabling her to leave her husband. Not entirely unexpected, the letter and subsequent confession proofed devastating for Mahler, who was ill with depression and guilt, and haunted by fear that Alma would leave him. Within a week, Gropius made an unannounced visit, and Mahler forced Alma to make a decision. In the event, Alma stayed with Mahler, yet continued her affair with Gropius. Mahler in turn, made an appointment with Sigmund Freud!

The 2010 film “Mahler on the Couch” provided a fictional reconstruction—dressed up as a grand historical drama—of the famous therapy session involving Sigmund Freud and Gustav Mahler! We do know that the meeting actually did take place, but how did it all come about? Merely one month after his daughter Maria Anna had died as the result of scarlet fever and diphtheria in the summer of 1907, Gustav Mahler was diagnosed with a potentially fatal heart condition! Deeply shaken, the composer withdrew into a world of morbid visions and deep trauma. As you might well imagine, this did not have a positive effect on his already shaky marriage. Alma Mahler writes in her diary, “Work, exaltation, self-denial and the never-ending quest were his whole life…he noticed nothing of all it cost me. He was utterly self-centered by nature…” When Alma went for a spa holiday in the summer of 1910, she met the young architect Walter Gropius, widely regarded as one of the pioneering masters of modern architecture. They quickly engaged in a passionate and all-consuming affair, and one day a love letter from Gropius ended up in Mahler’s hands. In fact, Alma accused Gropius of intentionally misaddressing the envelope in order to expose the affair and enabling her to leave her husband. Not entirely unexpected, the letter and subsequent confession proofed devastating for Mahler, who was ill with depression and guilt, and haunted by fear that Alma would leave him. Within a week, Gropius made an unannounced visit, and Mahler forced Alma to make a decision. In the event, Alma stayed with Mahler, yet continued her affair with Gropius. Mahler in turn, made an appointment with Sigmund Freud!

Actually, Gustav Mahler made a number of appointments with Sigmund Freud but canceled the first two! While the meeting was being arranged, Mahler was writing his 10th Symphony in his summerhouse in Toblach—in the Austrian province of Tyrol—and Freud was on holiday in the Dutch town of Leyden on the Baltic Coast. After an exchange of telegrams, Mahler traveled to Leyden and met Freud at a hotel; no famous consulting couch involved, I am afraid! Instead, the two men went on a four-hour walk through town. Freud later recalled how the composer made and broke two appointments before confirming the third. “I made an exception in receiving someone during my vacation, but for a man like Mahler…” Although Mahler had no previous experience with psychoanalysis, Freud later said that he had never met anyone who seemed to understand it so quickly. “I once analyzed Mahler for four hours,” reports Freud, “he had strong obsessions, I can tell you.” Of course, we don’t have a transcript of the conversation, but Freud’s initial diagnosis suggested, “Mahler sought a relationship with Alma modeled on an idealized image of his mother.” No surprise there, but as the walk progressed, Mahler suddenly realized why the most emotional passages in his music had so often been a mental block to his compositions. Those highly charged passages had always been ruined by the intrusion of some common and banal melody. According to Freud, it all went back to Mahler’s childhood. Mahler’s father had been exceedingly violent towards his mother. After a particular violent encounter, young Mahler ran away. When he reached the road, a street musician was cranking out a trite melody on his hurdy-gurdy. Ever since, Freud reasoned, “Mahler’s mind intertwined high emotion with light music.”

Actually, Gustav Mahler made a number of appointments with Sigmund Freud but canceled the first two! While the meeting was being arranged, Mahler was writing his 10th Symphony in his summerhouse in Toblach—in the Austrian province of Tyrol—and Freud was on holiday in the Dutch town of Leyden on the Baltic Coast. After an exchange of telegrams, Mahler traveled to Leyden and met Freud at a hotel; no famous consulting couch involved, I am afraid! Instead, the two men went on a four-hour walk through town. Freud later recalled how the composer made and broke two appointments before confirming the third. “I made an exception in receiving someone during my vacation, but for a man like Mahler…” Although Mahler had no previous experience with psychoanalysis, Freud later said that he had never met anyone who seemed to understand it so quickly. “I once analyzed Mahler for four hours,” reports Freud, “he had strong obsessions, I can tell you.” Of course, we don’t have a transcript of the conversation, but Freud’s initial diagnosis suggested, “Mahler sought a relationship with Alma modeled on an idealized image of his mother.” No surprise there, but as the walk progressed, Mahler suddenly realized why the most emotional passages in his music had so often been a mental block to his compositions. Those highly charged passages had always been ruined by the intrusion of some common and banal melody. According to Freud, it all went back to Mahler’s childhood. Mahler’s father had been exceedingly violent towards his mother. After a particular violent encounter, young Mahler ran away. When he reached the road, a street musician was cranking out a trite melody on his hurdy-gurdy. Ever since, Freud reasoned, “Mahler’s mind intertwined high emotion with light music.”

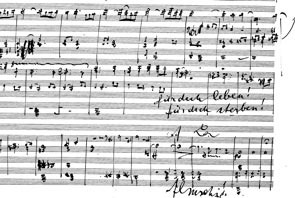

Seemingly, Mahler came away from the meeting feeling much better. Alma Mahler in her often fictional autobiography describes how her “husband realized that he had lived his life as a neurotic, and how the meeting calmed him down.” Modern views on the session have been mixed. On one hand, it is claimed that the “successful crisis intervention cured Mahler’s libido but stifled his creative ability.” Conversely, it has been suggested that Freud helped Mahler to channel his thoughts into his 10th Symphony. Littered with agonizing commentaries on the heart wrenching events of the summer, Mahler envisioned a 5-movement layout, and produced a nearly continuous sketch for the entire work. In reference to Alma he writes, “You alone know what it means; To live for you! For you to die! Almschi.” He completed the first movement marked “Adagio,” but a bout with bacterial endocarditis cut short his last artistic statement, and Mahler died in Vienna, on 18 May 1911.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 10, “Adagio”

More Anecdotes

-

Shaking for Queen Victoria What happened when Baroness Bloomfield was asked to sing for the Queen?

Shaking for Queen Victoria What happened when Baroness Bloomfield was asked to sing for the Queen? - A Tour Around Vienna

Suppé: Ein Morgen, ein Mittag, ein Abend in Wien A work by the youthful Suppé -

Desdemona in Real Danger What happened between Manuel Garcia and his daughter Maria Malibran?

Desdemona in Real Danger What happened between Manuel Garcia and his daughter Maria Malibran? -

Adelina Patti and Her Teacup Puppy How would you respond if you receive a Chihuahua puppy after a performance?

Adelina Patti and Her Teacup Puppy How would you respond if you receive a Chihuahua puppy after a performance?