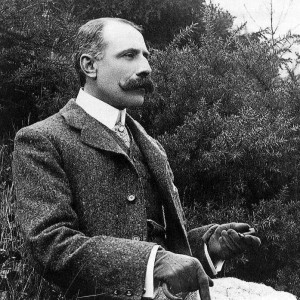

Edward Elgar

You don’t often think of Edward Elgar and Richard Strauss in the same way, but they were connected through the idea of the symphonic poem. Strauss’ symphonic poems such as Till Eulenspiegel and Don Quixote are well known but Elgar’s work in a similar vein, such as Falstaff, has fallen off many symphonic lists. The critic George Bernard Shaw regarded Falstaff as outclassing Strauss’ symphonic poems.

The character of Falstaff makes his first appearance in literature as the comedic courtier in Shakespeare’s Henry the Fourth, Part 1. He runs riot with the young Prince Hal, staging fake robberies, getting drunk, and hanging out in the disreputable East End, among other adventures. Upon the young prince’s ascension to the thrown as King Henry V, he puts away the things of his youth, such as the disreputable Falstaff. Falstaff, set aside, declines into a peaceful senility and dies.

Elgar divided the work into four sections to lay out the story:

1. Falstaff and Prince Hal introduces us to Falstaff and his young charge, Prince Hal.

Elgar: Falstaff, Op. 68: I. Falstaff and Prince Hal (English Northern Philharmonia; David Lloyd-Jones, cond.)

2. Eastcheap. The robbery at Gadshill. The Boar’s Head again. Revelry and sleep / Dream Interlude

Falstaff and Hal are entertained by ‘honest gentlewomen’ of the disreputable East End, represented by a musical theme for ‘Doll Tearsheet.’ Falstaff’s boastfulness and tale telling leads to the robbery attempt, where the men try to stage a robbery and end up robbing Falstaff instead. Revelry and sleep slow them down and we close with Falstaff’s snoring.

The Dream Interlude is Falstaff’s dreaming of his youth when he was page to the Duke of Norfolk and headed for a very different career than the shambles in which he now lives.

II. Eastcheap. The Robbery at Gadshill. The Boar’s Head Again. Revelry and Sleep

III. Dream Interlude

Eduard von Grützner: Falstaff mit großer Weinkanne und Becher (1896)

3. Falstaff’s March. The return through Gloucestershire. The new King and the hurried ride to London. / Interlude

Falstaff has been in the north recruiting an army, but all he brings back is an army of has-beens, his ‘scarecrow army,’ because he’s allowed the real soldiers to pay him off so they can escape service. The army is set to a limping theme, scarcely march material. At the end, news is received of the death of King Henry IV and all hurry to London. The second interlude returns us to the old-fashioned music of the pipe and tabor, again harkening back to Falstaff’s youth and the future that should have been.

IV. Falstaff’s March. The Return through Gloucestershire. The New King and the Hurried Ride to London.

V. Interlude: In Shallow’s Orchard

4. King Henry V’s progress. The repudiation of Falstaff and his death.

With his ascent to the throne, the new King’s military tone suddenly has backbone. Prince Hal’s theme, which we first heard at the beginning of the work is restated with a new authority (02:33). Falstaff is repudiated and cast aside, to die in a benign senility. The ending was described best by Elgar: “In the distance we hear the veiled sound of a military drum; the King’s stern theme is curtly thrown across the picture, the shrill drum roll again asserts itself momentarily, and with one pizzicato chord the work ends; the man of stern reality has triumphed.”

VI. King Henry V’s Progress: The Repudiation of Falstaff and His Death l

Elgar thought this work his finest orchestral piece but it’s rarely played in concert anymore. Although some critics, as mentioned above, ranked as one of the leading symphonic poems of the day, others, thought it too overblown. The humour of Falstaff was buried in the programmatic elements of the story. Even the dedicatee, the conductor Landon Ronald, who had conducted the premiere at the Leeds Festival in 1913, said that he “Never could make head or tail of the piece…” when speaking about it to fellow conductor John Barbirolli. Nonetheless, it’s an affectionate picture of the life of one of Shakespeare’s liveliest characters.