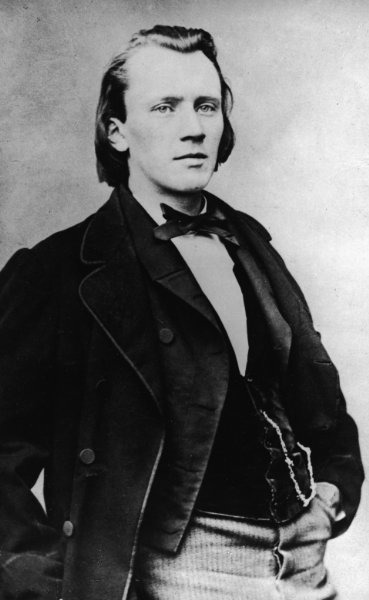

Brahms

Brahms was justifiably horrified, and immediately began to strictly censor his intended publications. Only three weeks after Schumann’s article, Brahms writes, “Above all it obliges me to exercise the greatest care in my choice of works to be published. I am contemplating not to publish any of my trios…” In addition, he began to self-consciously respond to criticism — even when his closest personal friends leveled it — by ruthlessly destroying or severely reshaping his compositions.

Piano Quartet No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 60

Emanuel Ax

Isaac Stern

Jaime Laredo

Yo-Yo Ma

This heightened sense of musical and personal insecurity is convincingly apparent in the tortured path of his Piano Quartet No. 3 in C minor. Begun in 1855, concurrent with first drafts for his first two piano quartets, Op. 25 and Op. 26, respectively, Op. 60 originally was cast in the key of C-sharp minor and comprised of only two movements.

A year or so later, Brahms had added a Scherzo movement, before putting the work aside for more than a decade.

By 1869 he returned to the composition and assigned it his Op. 54. However, Brahms was still not entirely satisfied and banished the work to his drawer for an additional four years.

In the winter of 1873/74 Brahms took heart and with much encouragement from his surgeon friend Theodor Billroth forced the composition into near-final shape. Exhaustedly Brahms reports, “This quartet has communicated itself to me only in the strangest ways.”

After a couple of minor revisions in the summer of 1874, Brahms handed the manuscript to his publisher Fritz Simrock. Yet he remained deeply dissatisfied with the work, asking Simrock to “attach an appropriate picture on the title page, for example, my head with a pistol before it. Now you can form an idea of the music! For this purpose I will send you my photograph!”

Essentially then, what we do hear in today’s performances is an opening and an Andante movement dating from 1855/56, a Scherzo from somewhere between 1857 and 1861, and a Finale from 1874. And in case you are wondering, the change of key to C minor was part of the final set of revisions in 1874 as well. As such, the work combines youthful exuberance with sophisticated musical textures and an entirely logical way of constructing motives and controlling their subsequent development and continuation.

However, it is still the emotional world of a twenty-year old deeply torn in his admiration for a dying Robert Schumann yet concurrently hopelessly in love with his wife Clara.

20 years on, Brahms had acquired all the technical skills of a seasoned composer but was unsure if he should ever release a work whose inspiration originated in the emotional conflicts of his past.

Since time heals all wounds, however, Brahms eventually did issue this most powerful and most intimate musical expression. He sarcastically described the work as “half old, half new — the whole thing isn’t worth much!”

I should think that most people would tend to whole-heartedly disagree with this statement.

The Quartet will be performed at the Hong Kong International Chamber Music Festival Opening Night Gala, 15 January 2014

Official Website