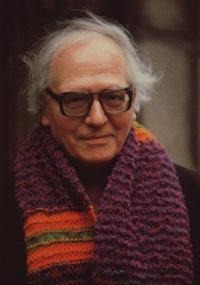

Olivier Messiaen

These are just a few of the questions that are asked when a new work is commissioned.

What, then, do you get when these constraints get thrown out the window, when the composer is given free reign over what to write? One of the most extreme and famous examples of this was when, in 1946, the Boston Symphony Orchestra commissioned Olivier Messiaen to write them a new work. They declared that he had total control over the length, instrumentation and subject matter of the work. There were no restrictions. And that, my friends, was how the Turangalîla-Symphonie was born.

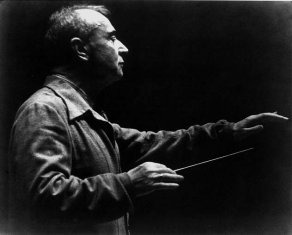

The principal conductor of the Boston Symphony orchestra, Serge Koussevitzky, commissioned the work, but Leonard Bernstein ended up conducting the premiere, due to an illness on Koussevitzky’s part, which took place on 2nd December 1949. The word ‘Turangalila’ derives from two sanskrit words: ‘turanga’ meaning ‘time’, and ‘lila’, a word with a complex meaning involving love and the way in which it interacts with life and death.

A work such as this (based, put simply, on the concept of overwhelming love, joy and ecstasy) can seem a bit dense at first. There’s a lot to get your ears around, but it’s really worth getting to know as it’s a great milestone in the twentieth-century orchestral repertoire.

Firstly, Messiaen uses a solo piano part throughout, making the piece feel like a piano concerto at points. Listen out for the extended cadenza half way through the Introduction to see what I mean! After this cadenza, notice how Messiaen simply uses three ideas (each with a totally different character) to tie the section together: a machine-like march in the basses and winds; a continuous searing string chorale in the background; stabs in the piano and brass. Through recognising these distinct sections and seeing how they’re juxtaposed, it’s easier to become familiar with the structure of the movement. However, the great thing is that because of how quickly this kaleidoscope of sounds changes, and the level of detail of each individual character, you never hear it in the same way twice. Pretty heavy going, right?

Serge Koussevitzky

I like to hear Turangalila in terms of ‘characters’. This contrast of characters pervades the whole work – you only have to look at the next movement, Chant d’Amour 1, to see this. After a dissonant introduction, the music is joyful, ecstatic. Just after you get to grips with this, though, the craziness stops and is replaced with something utterly calm and serene, a beautiful violin melody in F-sharp major. Cleverly, Messiaen often introduces major keys (something we all recognise) after highly dissonant sections, giving a sort of ‘oasis in the desert’ feel. Mmm, F-sharp major!

In this movement, we also hear the other solo keyboard instrument of the work: the ondes martenot. This is a keyboard synthesizer-ish instrument, capable of smoothly glissando-ing over its entire range. Listen out for it swooping down over the solo violin trill!

It’s impossible to debunk the whole piece in a matter of paragraphs, but it’s much easier to get a feel for it by focussing on the character of the music. Messiaen is a master orchestrator, so really try to enjoy the sounds he makes – they’re quite unlike anything else.

Also, don’t forget to bask in the joy of tonality when it arrives. The fact that it’s often after intensely dissonant music makes it all the more enjoyable! Personally, the most amazing moment of this is at the end of the fifth movement, Joie du Sang des Etoiles (Joy of the Blood of the Stars – what a title!). The F-sharp major chord after the blistering piano cadenza is truly spectacular.

Phew, you’ve just completed the crash course to the Turangalîla-Symphonie. How do you feel? Confused? Disoriented? That’s how I felt when first listening through to this masterpiece, but stick with it – it’ll be worth it.