Ravel’s composition ‘La Valse’, written at the close of World War I, can be seen as a parable of the violent death of 19th century Vienna – with “the waltz, long a symbol of gay Vienna, becoming in the composer’s hands a frantic Danse Macabre” (Carl Schorske – Fin de Siècle Vienna – Politics and Culture, Vintage Book Edition 1981, pp. 3 and 4). Ravel himself wrote: “I feel this work as a kind of apotheosis of the Viennese waltz, linked in my mind with the impression of a fantastic whirl of destiny”. Indeed, the composition opens with the introduction of different individual parts which then unify into the whole. Slowly, different elements are introduced: “fragments of waltz themes, scattered over a brooding stillness. Gradually the parts find each other — the martial fanfare, the vigorous trot, the sweet obligato, the sweeping major melody. Each element is drawn, its own momentum magnetized, into the wider whole… The pace accelerates; almost imperceptibly the sweeping rhythm passes over into the compulsive, then into the frenzied … At the very end, when the waltz crashes in a cataclysm of sound, each theme continues to breathe its individuality, eccentric and distorted now, in the chaos of totality” (Schorske, ibid) — with harmony becoming cacophony.

La Valse (version for Orchestra)

Berlin Symphony Orchestra / Gunther Herbig

Indeed, philosophers, writers, artists and musicians at that time felt the dissolution of their universe as intensely as Ravel conveys in ‘La Valse’, and nowhere else in Europe were these changes so deeply felt and compressed as in Vienna in the years from about 1890 to about 1938.

In this article, I will concentrate on the events starting at the beginning of 19th century which are fundamental to understanding Vienna’s Fin de Siècle culture, with its profound changes in architecture, art and music, which will be the focus of my next three articles over the next several months.

The French Revolution in 1789 precipitated the fall of the Ancien Régime with ramifications for monarchies and societies in the rest of Europe. In the Habsburg Empire, Francis I had to resign as Holy Roman Emperor (with ‘encouragement’ from Napoléon I), and was reduced to being just Emperor of Austria. The rise of the liberal middle class, with its demands for constitutional reforms, and the demands of workers for their rights, spurred by the Industrial Revolution, were expressed in the revolutions of 1830, 1848 and 1868. In architecture, art and music the changes from the Classical to the Romantic period, which I have discussed in previous articles, also had significant impact. Artists, musicians and writers, formerly employed at the royal courts of Europe, were now obliged to seek independent employment — as was the “First Generation” in Vienna — Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert.

In Austria, the early 19th century is generally known as the Biedermeier period. The name itself is taken from a literary character (from Vienna’s Fliegende Blätter) – ‘bieder’ – translated as ‘simple’, and ‘meier’ as any ‘Jones or Smith’ – any ordinary man. In architecture and furniture, the Biedermeier style was usually seen as a poor copy of the aristocratic style of the salons of royalty – although today Biedermeier furniture commands exorbitant prices in auction houses.

Paintings of the period also reflect a changed subject matter – here ‘Wine, Women and Song’ – ordinary Viennese in the countryside, enjoying themselves. The subject matter of genre paintings in general changed to ordinary people, showing them during their daily activities, such as a flower seller; cityscapes, such as Vienna’s Naschmarkt (food market), but also depicting the destitute, the disadvantaged, living on the margin of Viennese society.

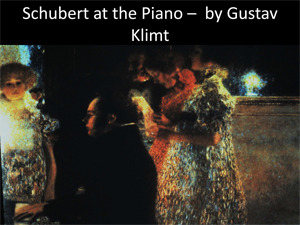

Turning to music, Franz Schubert was the only native Viennese amongst the composers of the ‘First Generation’. He was a Vienna Choirboy, but later turned to composing, when his voice changed. Schubert surrounded himself with a circle of friends including Johann Michael Vogl (famous baritone who performed Schubert’s Lieder/Songs), Anselm Hűttenbrenner (composer), Franz von Schober (actor) Johann Mayrhofer (poet), Joseph von Spaun (friend and financial supporter) and painters Leopold Kupelwieser and Moritz von Schwind. Known almost only through his songs, most of Schubert’s major compositions were neither published nor performed in his lifetime.

Winterreise

Hans Hotter

Gerard Moore

Schubert and his friends would meet for musical evenings (called ‘Schubertiade’) including games and excursions to the Vienna Woods, escaping overcrowded Vienna, where death, disease and poverty were all too present. Schubert’s song cycle, Die Winterreise, which he was still editing before his untimely death, has the theme of death/winter central to the composition. The titles range from ‘Frozen Tears, Solitude, The Raven, Last Hope, The Hurdy Gurdy Man’, just to name a few. Piano and voice are equal elements in the composition. In the Hurdy-Gurdy Man, the sparseness of the piano and voice conveys a profound image of death and stillness, which is, of course, the very essence of the Winterreise – a journey through a winter landscape, a metaphor for the end of life.

Many of the societal and cultural changes in the early years of the 19th century would lead to the great upheaval which brought on the revolutions of 1848 – in which workers and the liberal middle class rose in opposition to Chancellor Fűrst Metternich and Emperor Ferdinand I, who resigned in favor of his nephew, Franz Josef. During his reign, the city of Vienna became what it is today – with the ‘Ringstrasse’ (Ringstreet) buildings bringing a physical and psychological transformation important to the evolution of the Fin de Siècle culture – which will be the subject of my next article.