What is Ravel’s La Valse about? Is it a portrait of the disintegration of decadent pre-First War Europe, the dying embers of the Belle Epoque? Or simply a rollicking dance, a sensuous hommage to the Viennese Waltz?

Viennese Waltz

But by 1919 everything had changed, the composer himself profoundly affected by his wartime experiences. Vienna was a city shattered by war, in the grip of famine, and the waltz a bitter, poignant reminder of a vanished era. The impresario Sergei Diagheilev requested Ravel write La Valse, but it wasn’t the work he expected and he refused to stage it, claiming it was “not a ballet” but “a portrait of a ballet”. Ravel published the piece as a “choreographic poem for orchestra”, and the first performance of the orchestral version was in December 1920 in Paris. The work was eventually danced in Antwerp in 1926 by Ida Rubenstein’s troupe (which also premiered Ravel’s Bolero).

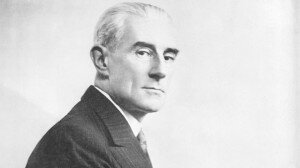

Ravel: La Valse

Maurice Ravel

But Ravel denied the work had any symbolic meaning, describing it as “a dancing, whirling, almost hallucinatory ecstasy, an increasingly passionate and exhausting whirlwind of dancers, who are overcome and exhilarated by nothing but ‘the waltz.’”

***

Ravel transcribed the orchestral version for two pianos and piano solo, and the very first performance of the work was actually given in its two-piano form, with Ravel as one of the performers.

Here a pianist friend of mine, who plays in a piano duo, reflects on the experience of learning and performing La Valse:

“Learning the two-piano version of La Valse was a treat. When Neil first suggested that we learn La Valse, I thought it might be beyond us, but we both worked hard at our parts over several months, and to our amazement it gradually came together…

As for performing La Valse, the orchestral version is of course familiar from many recordings and concerts, and in the back of one’s mind is the sound of the different instruments in Ravel’s orchestration. At first I felt very conscious of how the cellos and double basses, the two harps, the brass, or the woodwind, would sound at different points in the score.

But in fact as a pianist, you can enjoy being yourself in this music, without needing to mimic an orchestra all the time: the richness of Ravel’s two-piano sound provides plenty of tonal palette to work with, and much of the pleasure of learning the piece was learning to exploit to the full the contrasts in sound that one can achieve. We enjoyed the challenge of handing melodies from one piano to the other, trying to make the dynamics merge seamlessly between two instruments, learning to be really hushed and mysterious, or hushed and threatening, and conjuring the lilt of the Viennese waltz rhythm.

The final few pages certainly are extraordinary, as the waltz music seems to disintegrate into fragments and accelerates towards a wild climax. As a pair of pianists, you have to hold your nerve, and careful preparation was really essential to be confident that our parts would really fit together and not fall to bits. It was a balance between being accurate and careful, but somehow also letting caution fly to the winds to convey a sense of whirling excitement. In fact, of course, as so often in piano music, the trick was to be really on top of the part, so that you just knew that it would work every time: then you could remain calm and in control, but grasping the music with determination and energy so that the audience felt gripped and excited, not us!”. Julian Davis

“Through whirling clouds, waltzing couples may be faintly distinguished. The clouds gradually scatter: one sees […] an immense hall peopled with a whirling crowd. The scene is gradually illuminated. The light of the chandeliers bursts forth […]. Set in an imperial court, about 1855.” Maurice Ravel

Whatever one’s interpretation of La Valse, there is no doubt Ravel masterfully achieves his vision in the music.

Ravel has never truly revelaed the exact meaning for purpose of “La Valse”? Same true of the pop song, “Ode To Billy Joe.? HUmans demand finality and thus, what they cannot figure out, they invent to create finality which is rarely reality.