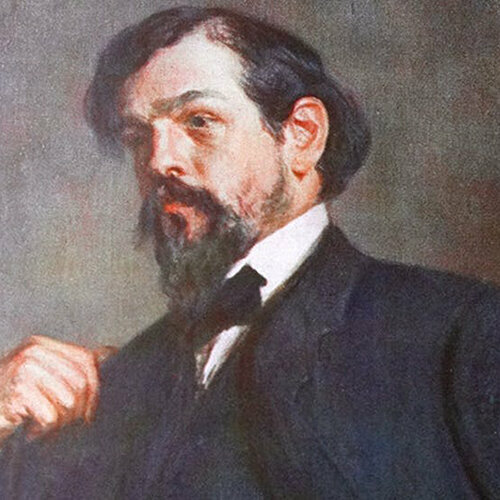

Claude Debussy photographed by Félix Nadar (1909)

Debussy wrote two books of 12 Preludes, and wrote them very quickly. Book I was begun in December 1909 and completed in February 1910 and Book II was started at the end of 1912 and finished in early April 1913.

By the time Debussy took up the prelude it had shed its earlier connection as ‘something that comes before something else’ – such as in Bach’s Preludes and Fugues. Now, Prelude had taken on the meaning of a kind of characteristic pieces – collections of music that explored anything from particular moods to technical problems. Because he didn’t want the performer to prejudge the music, Debussy did not label these works at the beginning of the piece, but put his titles at the end of the piece.

It is common now to think of Debussy’s Preludes as a group, but Debussy did not regard them as such and certainly didn’t wish them to be performed as a set. The most common way you hear them on programs is as a selection of 3 or 4 together, chosen by the performer and ordered to his own concept. Nonetheless, it is welcome to have a single recording of them, simply to get all the works in one place – and with the modern playlist, the listener can put them into his own order.

Debussy’s titles seem to put place us in the middle of the impressionist period – we have pieces that touch all the senses: perfume on the evening air, fireworks, footprints in the snow, a view of the girl with the flaxen hair, and other fleeting sounds and images. These are pictures in words and through his music, we can create those pictures in our imagination.

Everyone has favourites in these collections. One work that sets its mystery at the fore is The Sunken Cathedral (Book 1, No. 10: La cathédrale engloutie). The titles comes from a Breton story where a cathedral, submerged off the coast of the Island of Ys, periodically rises up from the sea. The beginning of the work in open fifths gives us a sound image of the cathedral and its attendant religious ceremonies: priests chanting, bells chiming, and the organ playing, emerging from the depths and at the end of the piece, it all sinks back again.

Debussy, La cathédrale engloutie. Philippe Bianconi, piano

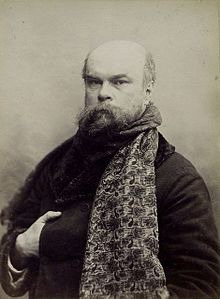

Arthur Rackham: The Fairies are Exquisite Dancers

Debussy, Voiles. Philippe Bianconi, piano

A work that leaves abstraction far behind is Hommage a S. Pickwick Esq. P.P.M.P.C. (Book 2, No. 9). This picture of Dickens’ immortal character, Samuel Pickwick, P.P.M.P.C. (Perpetual President–Member of the Pickwick Club) begins with a melody that sets this personality: a solemn version of ‘God Save the Queen,’ albeit with non-standard crashes interpolated. Even from this humorous beginning, we hear the same kind of crashes that the Pickwick Club encountered in The Pickwick Papers.

We have Dickens, we have Shakespeare (Book 1, No. 11: La Danse de Puck), we even have J.M. Barrie (Book 2, No. 4: ‘Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses’) based on an illustration in Peter Pan done by Arthur Rackham.

Debussy, ‘Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses’. Philippe Bianconi, piano

Inspiration from the musical world comes not only through the church music of The Sunken Cathedral but also in Minstrels, depicting black street musicians that Debussy had heard in England. In this we can hear the influence of popular music in its skewed rhythms coming from jazz.

Debussy, Minstrels. Philippe Bianconi, piano

One of the most famous of the works in this collection is La fille aux cheveux de lin (Book 1, No. 8: The girl with flaxen hair). A gently evocative piece, it has been transcribed for a seemingly infinite number of ensembles.

Debussy, La fille aux cheveux de lin. Philippe Bianconi, piano.

We’ve been looking at the collection of Debussy’s complete Préludes, as recorded by Phillippe Bianconi and we have Bianconi’s subtle readings of the subtle works in these collections, such as Voiles and Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir. We also have his less-successful readings of the more outgoing pieces, such as La dance de Puck, but, overall, this is a masterful recording that takes its place with the best of Debussy Prélude recordings.

Official Website