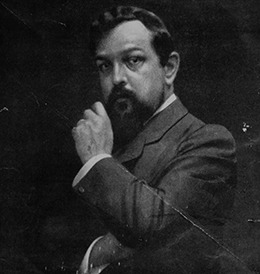

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

L’isle joyeuse

Cythera is a Greek island in the Mediterranean which, according to Greek mythology, is the island of Aphrodite, goddess of sensual and erotic love. The Berlin version of Watteau’s painting shows a statue of Aphrodite on a pedestal placed against a dark landscape of lush trees looking down on Cupid, a quiver of arrows in her hand. A multitude of couples are surrounded by putti, some below the statue, others moving seemingly toward a ship, the existence of which is only implied by its furled sails in the background. The dark trees on the right contrast with the ethereal lit background where the ship is moored — we cannot see beyond it. The question is whether the couples are leaving the island of Cythera or whether they are leaving the mainland for the island of Aphrodite – Watteau leaves the interpretation open for the viewer.

Embarkation to Cythera – Jean-Antoine Watteau – Berlin Version

Debussy starts his composition of ‘L’Isle Joyeuse’ with a short and lively introduction, ‘Quasi una cadenza’, followed by the theme of dancing rhythms, similar to the movements of the festively attired couples in the paintings — rococo decorations in sight and sound. Debussy moves on to a somewhat ‘rocking’ 3/8 meter which might suggest the movement of ship. He marks this section as ‘undulating and expressive’, accelerating the rhythm and combining it with extraordinary orchestral sonority bringing the composition to a rousing, sonorous conclusion.

The French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) was also inspired by Watteau’s painting in the Louvre. His poem, bearing the title ‘Un voyage à Cythère’ starts out setting the theme very much in accordance with the images projected by Watteau:

Embarkation to Cythera – Louvre version

Le navire roulait sous un ciel sans nuages/Comme un ange enivré d’un soleil radieux’.

(My heart, like a bird, fluttered happily about/And floated freely around the ropes;

The boat rolling under a cloudless sky/Like an angel drunk from a radiant sun).

Throughout the early part of the poem, Baudelaire continues to laud the beauty of the island, but then starts to oppose its mythological past with the present, which takes on a much more sinister role:

‘Habitants de Cythère, enfant d’un ciel si beau/Silencieusement tu souffrais ces insultes

En expiation de tes infâmes cultes/Et des péchés qui t’ont interdit le tombeau’.

(‘Habitants of Cythera, children of a beautiful sky/Silently you suffered these insults

Expiring from your infamous worship/And your sins which banned you from the tomb’).

In the poem’s last strophes, Baudelaire implies that love in general causes moral and physical suffering and that the landscape, though beautiful and charming, only speaks to him of his own torments:

Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867)

–Ah! Seigneur! donnez-moi la force et le courage/De contempler mon cœur et mon corps sans degoût’

(On your island, oh Venus! I found nothing standing but symbolic gallows where my image was suspended/ — Oh! Lord! Give me the strength and the courage/To contemplate my heart and body without disgust’).

Baudelaire speaks as ‘le poète maudit’ — the cursed poet — modern man — going well beyond the images and ideas that Watteau’s painting implies, and also quite different from Debussy’s situation on an island with his lover. Painting, music and literature can rarely give us a universal answer – they leave it to us to find our own interpretation.