Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) and Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) were two of the composers most familiar to me in my youth, with their oratorios, concerti grossi and choral compositions, respectively, heard particularly during the Christmas Season. Today’s article will reflect on some of their works which are representative not only of the differing southern and northern Baroque styles in music, but can also be linked to different concepts in architecture.

Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) and Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) were two of the composers most familiar to me in my youth, with their oratorios, concerti grossi and choral compositions, respectively, heard particularly during the Christmas Season. Today’s article will reflect on some of their works which are representative not only of the differing southern and northern Baroque styles in music, but can also be linked to different concepts in architecture.

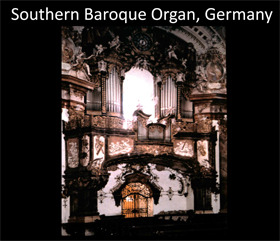

The Baroque period spans from the 16th to the middle of the 18th century and is usually seen as the art of the Counter-Reformation. In church buildings, there was a revival of the basilica form, such as Rome’s Chiesa del Gesú, in which priests and the public share the space of the rotunda. Heavily concave and convex ornamentation, lavishly gilded and painted interiors, dramatically placed statues lit by chiaroscuro in a complex architectural space, and soaring cupolas emphasize the move towards the supernatural, sensuous and illusionary. These churches, found not only in Italy but also in Germany’s Catholic southern regions, provided perfect acoustics for the music of the period. However, many Italian architects working in Germany’s south saw the organs as part of the decoration of the church, fitting them into spaces between windows, which placement affected their range and power. Many of these organs could only be used for improvisations. In Germany’s northern and eastern regions however, different principles in architecture and organ building prevailed.

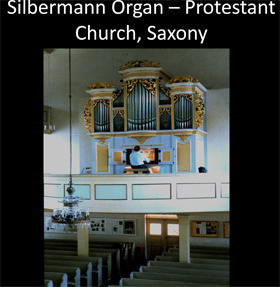

In Italy, (and in particular during his time in Rome) Arcangelo Corelli was recognized not only as one of the most famous composers and celebrated violinists, but also as one of the most influential teachers of generations of composers, such as Händel, Vivaldi, Geminiani and many others. Corelli was particularly noted for the beautiful singing tone of his violin playing, typical of the Italian musical tradition in which the cantabile always dominates. Many of his contemporaries, as well as later generations of violinists well into the 19th century, considered Corelli the founder of modern violin technique. It is important to note that his style and technique were facilitated by the instruments produced by the most famous violin makers of all times, the Amati, Guarneri and Stradivari families, all situated in Cremona, Italy. In a similar vein, the instruments produced by the great organ builders of Germany, Arp Schnitger and Gottfried Silbermann, inspired composers such as Buxtehude and Johann Sebastian Bach to compose organ works which were able to make use of the full and varied majestic tonalities of these remarkable instruments.

In Italy, (and in particular during his time in Rome) Arcangelo Corelli was recognized not only as one of the most famous composers and celebrated violinists, but also as one of the most influential teachers of generations of composers, such as Händel, Vivaldi, Geminiani and many others. Corelli was particularly noted for the beautiful singing tone of his violin playing, typical of the Italian musical tradition in which the cantabile always dominates. Many of his contemporaries, as well as later generations of violinists well into the 19th century, considered Corelli the founder of modern violin technique. It is important to note that his style and technique were facilitated by the instruments produced by the most famous violin makers of all times, the Amati, Guarneri and Stradivari families, all situated in Cremona, Italy. In a similar vein, the instruments produced by the great organ builders of Germany, Arp Schnitger and Gottfried Silbermann, inspired composers such as Buxtehude and Johann Sebastian Bach to compose organ works which were able to make use of the full and varied majestic tonalities of these remarkable instruments.

Violin Sonata in D Minor, Op. 5, No. 12, “La folia”

Two of the most beautiful compositions by Corelli are his Violin Sonata, ‘La Folia’ in D-Minor, op. 5, No. 12 and his Concerto Grosso in G-Minor, Op.6, No. 8, ‘Fatto per la note di Natale’ (‘Made for the Night of Christmas’). ‘La Folia’ is based on a Portuguese dance (a fertility rite) first mentioned in the literature of the 15th century, in which dancers carried men dressed as women upon their shoulders. The rapid rhythm, as well as his slightly ‘mad’ form of the dance, gives it its name. A certain melody forms its base and is then taken over by a certain number of other themes — as a theme and its variations — in Corelli’s composition, a theme and 23 variations. This composition made him famous all over Europe and became an inspiration for many composers in the following centuries, reflected in works of Liszt, Paganini and Rachmaninov.

Two of the most beautiful compositions by Corelli are his Violin Sonata, ‘La Folia’ in D-Minor, op. 5, No. 12 and his Concerto Grosso in G-Minor, Op.6, No. 8, ‘Fatto per la note di Natale’ (‘Made for the Night of Christmas’). ‘La Folia’ is based on a Portuguese dance (a fertility rite) first mentioned in the literature of the 15th century, in which dancers carried men dressed as women upon their shoulders. The rapid rhythm, as well as his slightly ‘mad’ form of the dance, gives it its name. A certain melody forms its base and is then taken over by a certain number of other themes — as a theme and its variations — in Corelli’s composition, a theme and 23 variations. This composition made him famous all over Europe and became an inspiration for many composers in the following centuries, reflected in works of Liszt, Paganini and Rachmaninov.

Concerto Grosso in G Minor, Op. 6, No. 8, “Christmas Concerto”

Corelli’s ‘Christmas Concerto’ is structured as a ‘sonata da chiesa’ (‘church sonata’), usually played in church as overture before the Mass, but extended here from the typical four to a six movement structure. The ensemble consists of two violins, a cello and a larger tutti ensemble where the slow-fast-slow structure is reversed – a six-measure fiery Vivace prefaces the opening Grave movement; the third Adagio movement has a central Allegro episode and many other tempi changes occur throughout the piece. The lovely, serene Pastorale (Largo) which concludes the composition — very typical of the true Italian ‘bel canto’ style – has become the most famous movement of all. In the German tradition, particularly in the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, we see a very different development.

Corelli’s ‘Christmas Concerto’ is structured as a ‘sonata da chiesa’ (‘church sonata’), usually played in church as overture before the Mass, but extended here from the typical four to a six movement structure. The ensemble consists of two violins, a cello and a larger tutti ensemble where the slow-fast-slow structure is reversed – a six-measure fiery Vivace prefaces the opening Grave movement; the third Adagio movement has a central Allegro episode and many other tempi changes occur throughout the piece. The lovely, serene Pastorale (Largo) which concludes the composition — very typical of the true Italian ‘bel canto’ style – has become the most famous movement of all. In the German tradition, particularly in the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, we see a very different development.

The Lutheran Reformation, begun in 1517, changed the religious musical tradition in Germany in the extensive use of chorales in church services, (which were now in German with the active participation of the general public), in the architecture of Protestant churches and in the development of organs as free-standing instruments by the greatest organ builders of all times, Arp Schnitger and Gottfried Silbermann. Protestant churches in the Baroque style still emphasized concave and convex movement in their architectural elements, but were designed with simple, white interiors. The magnificent organs of the time, often ‘tested’ by J. S. Bach as to their ‘lung capacity’ i.e., wind power, became the perfect instruments for his organ compositions. Bach’s ‘Christmas Oratorio’, BWV 248, is a perfect illustration of his use of secular chorales (which he had used in earlier compositions), now reused in a religious composition. Their polyphonic, fugal structure creates beautifully fitted architectural blocks — voices and instruments — ‘frozen architecture’, where every note counts and where, with the simplest means, the greatest effect is achieved. For Bach and many other German Baroque composers, a sense of order prevailed which found its perfect expression in the fugue, canon and passacaglia embodying fundamental form, pattern and unity.

The Lutheran Reformation, begun in 1517, changed the religious musical tradition in Germany in the extensive use of chorales in church services, (which were now in German with the active participation of the general public), in the architecture of Protestant churches and in the development of organs as free-standing instruments by the greatest organ builders of all times, Arp Schnitger and Gottfried Silbermann. Protestant churches in the Baroque style still emphasized concave and convex movement in their architectural elements, but were designed with simple, white interiors. The magnificent organs of the time, often ‘tested’ by J. S. Bach as to their ‘lung capacity’ i.e., wind power, became the perfect instruments for his organ compositions. Bach’s ‘Christmas Oratorio’, BWV 248, is a perfect illustration of his use of secular chorales (which he had used in earlier compositions), now reused in a religious composition. Their polyphonic, fugal structure creates beautifully fitted architectural blocks — voices and instruments — ‘frozen architecture’, where every note counts and where, with the simplest means, the greatest effect is achieved. For Bach and many other German Baroque composers, a sense of order prevailed which found its perfect expression in the fugue, canon and passacaglia embodying fundamental form, pattern and unity.

The musical and architectural forms, as well as the character of the instruments crafted by the masters of the Italian Baroque mutually supported each other — as did those of the contrasting German Baroque tradition.

You May Also Like

-

Women in Baroque Music "London Festival of Baroque Music 2015" Women in music, either as composer, performers, or inspirational figures, are never celebrated enough.

Women in Baroque Music "London Festival of Baroque Music 2015" Women in music, either as composer, performers, or inspirational figures, are never celebrated enough. -

The Baroque Era – The Golden Age of the Organ The Reformation and Counterreformation of the 16th and 17th centuries had a decisive impact not only on the architecture of the time...

The Baroque Era – The Golden Age of the Organ The Reformation and Counterreformation of the 16th and 17th centuries had a decisive impact not only on the architecture of the time...

More Arts

-

Poetry and Music: Johann Paul Friedrich Richter “Jean Paul” (1763-1825) Find out how he inspired Schumann, Georg Friedrich Hass and more composers

Poetry and Music: Johann Paul Friedrich Richter “Jean Paul” (1763-1825) Find out how he inspired Schumann, Georg Friedrich Hass and more composers -

Musicians and Artists: Zwicker and Five Modernists Alfons Karl Zwicker: Vom Klang der Bilder

Musicians and Artists: Zwicker and Five Modernists Alfons Karl Zwicker: Vom Klang der Bilder -

Musicians and Artists: Staud and Pissarro Johannes Maria Staud's trio Sydenham Music

Musicians and Artists: Staud and Pissarro Johannes Maria Staud's trio Sydenham Music - What Was Left Behind

André Jolivet’s Mana Listen to this six-part piano work!