Elisabeth Schwarzkopf

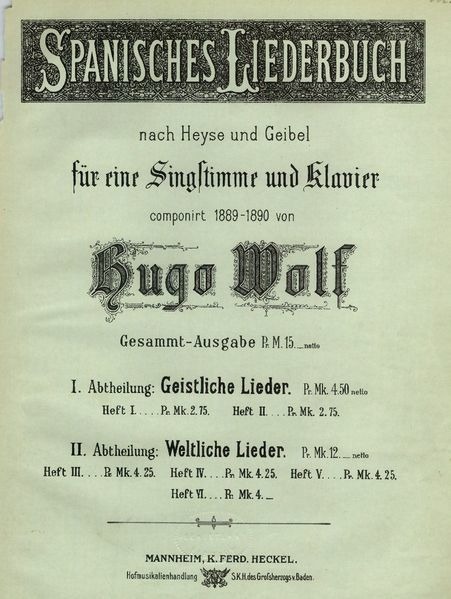

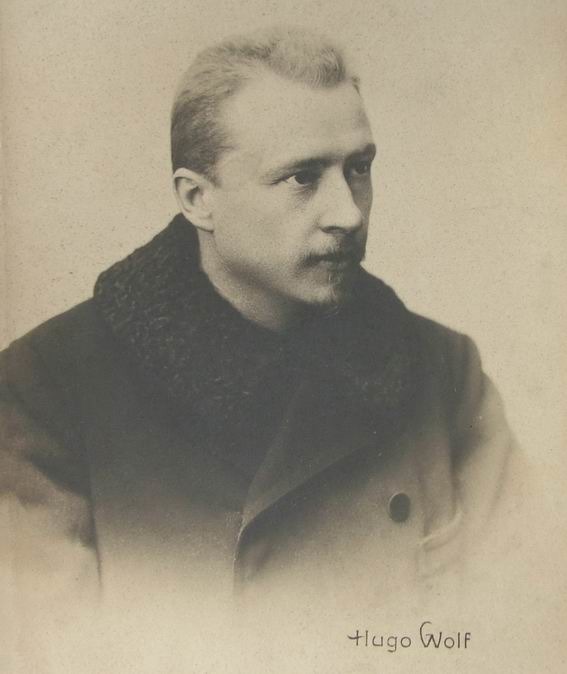

Hugo Wolf set the poetry in two parts: one set of 22 poems in 1892 and the second set of 24 poems in 1896. The collection is not a song cycle but rather a collection of songs from a single source. There’s no overarching storyline, such as we saw in Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin or Schumann’s Frauenliebe und –leben.

One of the greatest recordings of the 46 songs as a whole was done by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf in the 1960s, with Gerald Moore at the piano. Since the poems are from either male or female points of view, this pairing worked well.

One song in particular that Schwarzkopf’s performance comes through on is No. 11. Wie lange schon. She yearns for a musician as a lover and her boyfriend plays the violin. This is all very good, but then we hear in the conclusion by the piano just what kind of musician that violinist is. When you listen to the song again, you reinterpret her performance: she’s not happy about this lover, she’s bored and he’s excruciating.

Wolf: Italiensches Liederbuch: No. 11. Wie lange schon (Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, soprano; Gerald Moore, piano)

A happier song is No. 19. Wir haben Beide lange Zeit geschwiegen (We have both been silent a long time). She speaks of the fact that they have been silent because they have been divided by war – the angels of God have brought him back, brought her peace, and speech has come back to them as well. The song goes from a recitation on a single note, reacting dissonantly with the motion in the piano, to an expressive intimacy on her lover’s safe return.

No. 19. Wir haben Beide lange Zeit geschwiegen

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau with pianist Gerald Moore in 1967

No. 1. Auch kleine Dinge (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Gerald Moore, piano)

Most beautiful love song is No. 3. Ihr seid die Allerschönste weit und breit (You are the loveliest of all things). He says she’s more beautiful than all of nature: lovelier than the flowering meadows in May, more beautiful than the fountains at Viterbo, and so beautiful, full of charm and grace that even the cathedrals of Orvieto and Siena must bow down to her.

No. 3. Ihr seid die Allerschönste weit und breit

The last song for the man seems to be a complete change in style – almost a recitative in its presentation. He speaks to his absent lover, asking her if she knows how much he suffers for her as he waits for her on her doorstep. He is drenched in rain, lighting is all around, and, clearly she is not.

No. 44. O wüßtest Du, wie viel ich Deinetwegen

What came next for Wolf was a tragedy: five years after completing this collection his syphilis drove him insane and he spent his last years in an insane asylum.