William Langlie-Miletich

“Competitions are for horses, not artists,” composer Béla Bartók famously said, but winning can pay off big time. Tessa Lark who won the Klein competition in 2008 subsequently received the Naumburg International Violin Award, and this year she was the recipient of an Avery Fisher Career Grant. Violinist Frank Huang, first place winner in 1999, was recently selected as the New York Philharmonic’s new concertmaster, and the twenty-one year former child prodigy, Austin Huntington, who won the competition in 2012, was appointed principal cello of the Indianapolis Symphony in 2015. Jing Wang the winner in 2007, is now the concertmaster of the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra, and the intense, dazzling virtuoso, named Musical America’s 2016 Instrumentalist of the Year, violin soloist Jennifer Koh, won in 1993. Quite a track record for the competition! Here is an inside look!

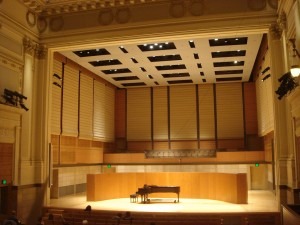

San Francisco Conservatory concert hall

Despite their youth, ranging in age from 15-23, much like Olympic athletes, the contestants have already weathered the competition circuit, winning other prizes, performing on radio programs, such as From The Top, and appearing in concert.

The candidates have been through endless rounds of adjudication and criticism. I feel the anticipation and responsibility keenly. The pros usually outweigh the cons—the artists’ intense preparation has resulted in musical, emotional, and technical growth. But on these particular two days, with the inevitable butterflies, who will have the will, tenacity, and concentration? The self-possession and poise? The ability to allow the music to flow through them, stirring souls and touching hearts?

One hundred applications were received early in the year. Each submitted a CD, which included solo Bach, a 20th or 21st century work and a major concerto. The candidates’ identities were kept strictly anonymous from the panel of judges who narrowed the field to 25 artists. Before mid-March, the adjudicators then sat down in a marathon session to hear the 25 candidates from whom they chose the nine semi-finalists. Once the instrumentalists were notified, the sheet music to the commissioned work was sent to them a mere 10 weeks before the finals. Also they had to quickly submit their precisely timed recital programs.

Coleman Itzkoff

The semi-finals were scheduled from 2:00pm-10:00pm. The judges had a chance to mingle, before Mitchel Klein, the Artistic Director, carefully went over the adjudication rules put in place almost forty years ago by Milton Preves—legendary violist, teacher, soloist and principal violist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for decades. Judges were to refrain from discussion. Voting was by secret ballot and was tallied after each round. At the end of the day we were to choose the three finalists and the winners of the prize for the best solo Bach performance and the best performance of the newly commissioned work.

With clipboards in hand, a program book without the candidate’s resumes, and evaluation sheets for any helpful comments we might have, we gathered in the beautiful San Francisco Conservatory concert hall sitting well away from each other and other audience members.

And we were off! Each candidate was warmly introduced. He or she played their 25-minute program without interruption.

Each candidate played their 20th century concerto, solo Bach and the virtuoso commissioned work. The level was astounding—brilliant playing of works as diverse as the Korngold violin concerto, the Bartók Concerto No. 2, the Victor Herbert and Elgar Cello Concertos, the Barber, Paganini No. 1 and Sibelius Violin concertos, and the Bottesini Bass Concerto No. 2. Choosing three finalists would be an extremely difficult choice.

After a short break before the evening session, former winner Tessa Lark spoke to the audience about why an artist puts himself or herself through this grueling process. “There are three reasons we put ourselves through this,” she explained, “the tremendous discipline and invaluable preparation required for this level of competition, the performance opportunities offered in addition to the monetary prizes, and the connections and “community” established during the process. She pointed out that the candidates are unique artists, “with beautiful messages to share.” The Klein Competition is unusual in their support of young artists. Each semi-finalist receives a prize of $1000. Two fourth place winners receive $1500, and the first three prizes come not only with a monetary award and performance opportunities but also future nurturing from the organization.

After the nine candidates performed we hurried out to our little room where we were sequestered for the voting. The organizers of the competition thought of everything. Ms. Lark and Michael Thurber, bass player for Jon Batiste’s band Stay Human on Colbert’s The Late Show, entertained the audience with a little bluegrass while everyone waited for the outcome.

Our anonymous voting went smoothly. All were in agreement as to whom to advance to the finals with one caveat—we wanted to hear four artists in the finals not the usual three.

It was nearly 10:00pm when the four finalists and winners of the best performances of Bach and the commissioned work were announced. We were exhausted. Imagine how pooped the candidates must have been. There was one more task—to draw straws to determine the order of playing for the finals the next day, and to arrange one last rehearsal with the accompanists. While the performances were still fresh in my memory, as soon as we returned to the hotel, I wrote my critiques hoping that my remarks would be beneficial to the young people in the future. The music swirled in my head all night. I know others slept little that night.

The following day before the official start time of the final round the jury met in our designated room to speak directly with the semi-finalists who did not advance. This type of valuable feedback is rare for a competition.

The finals, open to the public, were filled with music lovers, teachers, candidates and the finalists’ anxious family members.

Alina Ming Kobialka plays Barber at age 13

Our four finalists were violinists Alina Ming Kobialka and Evin Blomberg playing Sibelius and Bartók concertos respectively, cellist Coleman Itzkoff performing the Elgar Concerto, and double bass player William Langlie-Miletich playing Bottesini Concerto No 2. Each had prepared a thirty-five minute recital program, which included a sonata, additional movements of their concerto and if there was time, solo Bach or the Aquilanti work.

Coleman Itzkoff cellist plays “Julie – O” by Mark Summer

The technically brilliant young artists took my breath away. Gorgeous sounds, wonderful sonorities, great passion, beautiful phrasing, dark brooding sonorities, authentic interpretations, and musically poised performances elicited ovation after ovation.

William playing Bottesini on From the Top

Once again we hurried down to our private room to vote. All four were more than deserving of prizes. Overall artistic accomplishment, and emotionally poignant playing was the criterion for the winner. And the first prize went to bassist William Langlie-Miletich, 19, a dynamic performer equally comfortable in jazz and classical music. He is currently at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. Certainly I look forward to hearing all four of the musicians in the future. The stellar interpretations during the Klein competition remind me of the quote by Ludwig van Beethoven:

“Music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy.” There is no doubt that the future of music is in good hands.

More on the winner and the competition

Klein Competition short documentary