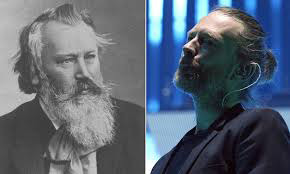

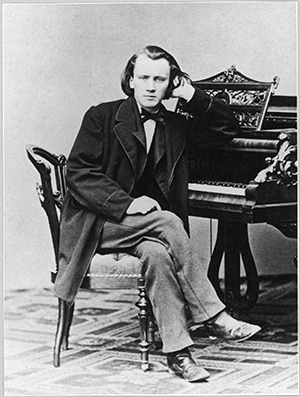

During his early compositional career, Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) exhibited a heightened sense of musical insecurity. He self-consciously responded to criticism, even when leveled by his closest personal friends, by ruthlessly destroying or severely reshaping his compositions. His Piano Quintet in F minor, opus 34, represents a convincing case in point. The work originated as a String Quintet, borrowing its scoring of 2 violins, viola and 2 cellos, from Franz Schubert’s famous C-major Quintet, D. 956. Joseph Joachim, who rehearsed the piece with friends, responded enthusiastically, yet found fault with its instrumentation. As a result, Brahms recast the work as a Sonata for 2 pianos, and eventually completed the work as a piano quintet. Brahms destroyed the original String Quintet version, but thanks to a reconstruction by Anssi Karttunen, we get a glimpse at what the original version might have sounded like.

During his early compositional career, Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) exhibited a heightened sense of musical insecurity. He self-consciously responded to criticism, even when leveled by his closest personal friends, by ruthlessly destroying or severely reshaping his compositions. His Piano Quintet in F minor, opus 34, represents a convincing case in point. The work originated as a String Quintet, borrowing its scoring of 2 violins, viola and 2 cellos, from Franz Schubert’s famous C-major Quintet, D. 956. Joseph Joachim, who rehearsed the piece with friends, responded enthusiastically, yet found fault with its instrumentation. As a result, Brahms recast the work as a Sonata for 2 pianos, and eventually completed the work as a piano quintet. Brahms destroyed the original String Quintet version, but thanks to a reconstruction by Anssi Karttunen, we get a glimpse at what the original version might have sounded like.

Johannes Brahms: String Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 (reconstructed A. Karttunen)

However you look at it, transcriptions for piano began with Franz Liszt. His arrival on the scene coincided with the development of the piano in increased power and sonority, and the growing popularity of the salon. Unsurpassed virtuosity and shameless showmanship aside, it was not always possible for the public to have easy access to repertory. By fashioning transcriptions of other composer’s music, Liszt introduced the public to some of the latest and hottest musical items on the market. Symphonies, themes from operas, organ works, chamber music and songs furnished a vast body of work for solo piano, either remaining entirely faithful to the originals, or more often than not appearing in highly embellished arrangements. Liszt produced roughly 170 song transcriptions, but he did not touch a single Brahms song. That thankful task was left to pianists of later generations.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Arrangement of Lieder (arr. Frederic Meinders)

5 Lieder, Op. 94: No. 4. Sapphische Ode (arr. for piano)

9 Lieder und Gesange, Op. 63: No. 5. Junge Lieder I (arr. for piano)

49 Deutsche Volkslieder, Book 1, WoO 33: No. 6. Da unten im Tale (arr. for piano)

4 Lieder, Op. 96: No. 2. Wir wandelten, wir zwei zusammen (arr. for piano)

5 Lieder, Op. 47: No. 1. Botschaft (arr. for piano)

5 Lieder, Op. 105: No. 1. Wie Melodien zieht es mir (arr. for piano)

Arnold Schoenberg insisted that his own compositions were only evolutionary, rather than revolutionary, and simply a logical extension of the German tradition. And Schoenberg decidedly thought that he was the true successor to Brahms. He started on his arrangement of the first Brahms piano quartet in May of 1937 in Los Angeles. When a music critic asked to why he had chosen the work in question, Schoenberg replied, “I like the piece. It is seldom played. It is always very badly played, because, the better the pianist, the louder he plays and you hear nothing form the strings. I wanted once to hear everything, and this I achieved.” Schoenberg changed none of the notes of the Brahms original, however, he did include some chromatic writing for the brass. As has rightfully been observed, “most of Schoenberg’s arrangements say more about him than they do about the music he was adapting. In the case of Brahms’s Op. 25, he was uncommonly respectful…In his arrangements of concertos by Handel and Monn he sought to remedy what he regarded as the deficiencies in Baroque style, here he was concerned with releasing a potentiality latent in the music, as several of Brahms’s early large-scale works, are budding symphonies.”

Arnold Schoenberg: Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor, Op. 25 (arr. for orchestra)

You May Also Like

-

Transfigured Brahms When Johannes Brahms delivered his Clarinet Sonatas Op. 120 to Richard Mühlfeld, he basically apologized for not having written a clarinet concerto.

Transfigured Brahms When Johannes Brahms delivered his Clarinet Sonatas Op. 120 to Richard Mühlfeld, he basically apologized for not having written a clarinet concerto. -

Brahms versus Pop A number of music critics have called Frank Sinatra the “greatest singer of the 20th century.”

Brahms versus Pop A number of music critics have called Frank Sinatra the “greatest singer of the 20th century.” -

Brahms in Disguise In music, nobody felt the anxiety of the past—specifically the looming shadow of Ludwig van Beethoven—more acutely than Johannes Brahms.

Brahms in Disguise In music, nobody felt the anxiety of the past—specifically the looming shadow of Ludwig van Beethoven—more acutely than Johannes Brahms. -

Arranged by Brahms Johann Jakob Brahms was a double bass player in the six-man band that performed daily at the Alster Pavilion, Hamburg’s most fashionable meeting-place.

Arranged by Brahms Johann Jakob Brahms was a double bass player in the six-man band that performed daily at the Alster Pavilion, Hamburg’s most fashionable meeting-place.

More Inspiration

- Fanciful Stories in Music

Dittersdorf: “Ovid Symphonies” I Six fun and fanciful symphonies by the Austrian composer - Musical Postcards: Albeniz’s Recuerdos de viaje A tour around Spain from the sea to the Alhambra

- A Tour of the Galaxy

Leopold van der Pals’ Mönch Wanderer: Sphären-Musik An impressionistic setting of the planets’ characters - World Piano Day 2024

The Persian Connection Find out how the piano was tuned and played based on Persian traditional music