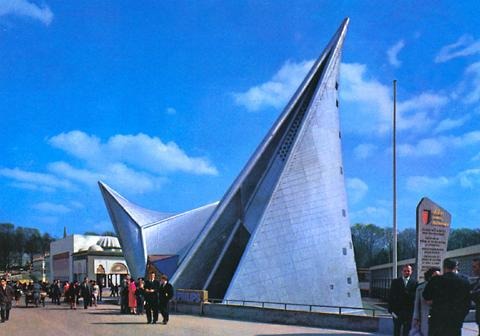

Surprising, as it may sound, some of the most intimate and convincing synergies between architecture and music were created in the 20th century. Take for example the “Philips Pavilion” designed to celebrate postwar technological progress for the World’s Fair Expo 1958 in Brussels. Originally, the office of Le Corbusier — the renowned architect, designer, painter, urban planner, and one of the pioneers of modern architecture — was charged with the design. However, Le Corbusier was busy with various projects in Europe and India, and handed the project to his assistant Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001).

Surprising, as it may sound, some of the most intimate and convincing synergies between architecture and music were created in the 20th century. Take for example the “Philips Pavilion” designed to celebrate postwar technological progress for the World’s Fair Expo 1958 in Brussels. Originally, the office of Le Corbusier — the renowned architect, designer, painter, urban planner, and one of the pioneers of modern architecture — was charged with the design. However, Le Corbusier was busy with various projects in Europe and India, and handed the project to his assistant Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001).

Born in Rumania to Greek parents, Xenakis soon became embroiled in the raging absurdity of WW2, and his active involvement against Churchill’s martial law in Greece left him badly injured and cost him his left eye. In 1947 he fled from Greece and came to Paris as an illegal immigrant. He managed to get a job at Le Corbusier’s architectural studio, but simultaneously attempted to study music with Nadia Boulanger, Arthur Honegger, and Darius Milhaud; he was quickly rejected. Eventually, he was allowed to join the composition class of Olivier Messiaen, who later wrote: “I understood straight away that he was not someone like the others. He is of superior intelligence. I did something horrible, which I should do with no other student, for I think one should study harmony and counterpoint. But this was a man so much out of the ordinary that I said… No, you are almost thirty and you have the good fortune of being Greek, of being an architect and having studied special mathematics. Take advantage of these things. Do them in your music.” And so Xenakis began to pioneer the use of mathematical models in music, and also became a hugely important influence on the development of electronic and computer music. He started to integrate music with architecture, “designing music for pre-existing spaces, and designing spaces to be integrated with specific music compositions and performances.”

Iannis Xenakis

Iannis Xenakis: Concret PH

Edgar Varèse’s: Poème électronique

I have read so many posts about the blogger lovers however this post is in fact a good

piece of writing, keep it up.