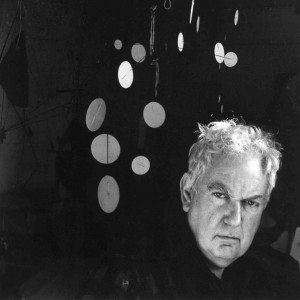

Alexander Calder (1898-1976)

In his youth, Calder had shown not only an interest in art, but also an interest in mechanical engineering and applied kinetics. Calder (1898-1976) had moved to Paris in 1926, where became friends with many of the leading artists and musicians, such as Fernand Léger, Jean Arp, Francis Picabia, Piet Mondrian, Marcel Duchamp, Eric Satie and Edgard Varèse. Paris in the ‘Roaring Twenties’ was an exciting time for artists — the Art Nègre (which had influenced Picasso and Matisse) and the Paris Jazz Age had brought many American performers and artists to Paris and to the lively Montparnasse quarter where Calder lived. The 1929 short film ‘Montparnasse – Where the Muses Hold Sway’ gives not only an idea of this interesting period in Paris, but also emphasizes the close relationship between artists and musicians, who drew inspiration from each other.

Montparnasse – Where the Muses Hold Sway

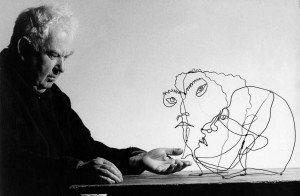

Calder with Wire Sculptures –‘Edgar Varese’ and ‘Untitled’, 1963

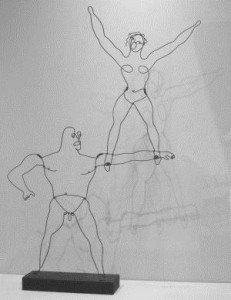

Many of his fellow artists were also interested in Calder’s creation of his miniature ‘Le Grand Cirque Calder’ – initially inspired by a two week stay with the Barnum and Bailey Circus in New York. Calder fashioned many of his puppets after the circus acrobats and tightrope walkers he had met, using wire, cloth, string, rubber, cork and other found objects. He performed with his circus, operating cranks and pulleys that activated trapeze artists, acrobats and animals — and roaring like a lion, and dropping “chestnuts” behind the performing elephant after which he ‘pooper-scooped’ them up. Every performance was unique – Calder, its magician, street performer and entertainer, always focused on the elements of change and chance — theatrical performance became second nature for him.

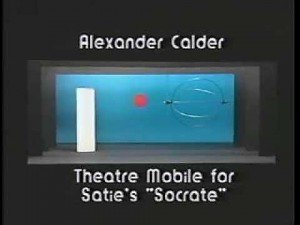

It was therefore not surprising that he was commissioned to create the set for Satie’s composition ‘Socrate: Three dialogues of Plato’ (orchestra and voice). The stage set consists of three elements, a red disk, interlocking steel hoops and a vertical rectangle, white on one side black on the other, against a blue backdrop. Calder filled the empty stage by moving these different objects as if they were dancing through space and time – with the flow of time controlled like an artistic enterprise. It would serve as inspiration for his subsequent work – his mobiles — the name provided by Marcel Duchamp.

It was therefore not surprising that he was commissioned to create the set for Satie’s composition ‘Socrate: Three dialogues of Plato’ (orchestra and voice). The stage set consists of three elements, a red disk, interlocking steel hoops and a vertical rectangle, white on one side black on the other, against a blue backdrop. Calder filled the empty stage by moving these different objects as if they were dancing through space and time – with the flow of time controlled like an artistic enterprise. It would serve as inspiration for his subsequent work – his mobiles — the name provided by Marcel Duchamp. Eric Satie – Socrate: Three dialogues of Plato

‘HI’ (Two Circus Acrobats), 1928

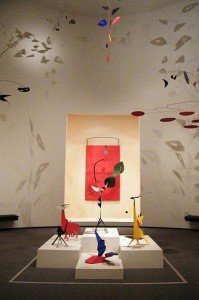

Calder Mobile – East Building of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Alexander Calder at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Edgard Varèse

Deserts: Third Electronic Interpolation (beginning)

Calder exhibit “Hypermobility” at the Whitney Museum, New York